“It is exciting to see this group tackle the climate crisis from a number of different angles. This discussion is especially relevant as we come off the end of the Global Climate Summit and as governments and other actors set new targets and lay out the groundwork for what the next 10 years of action will look like.”

– Tim McDonnell, 2016 Fulbright-National Geographic Storytelling Fellow to Kenya, Quartz magazine climate and energy journalist

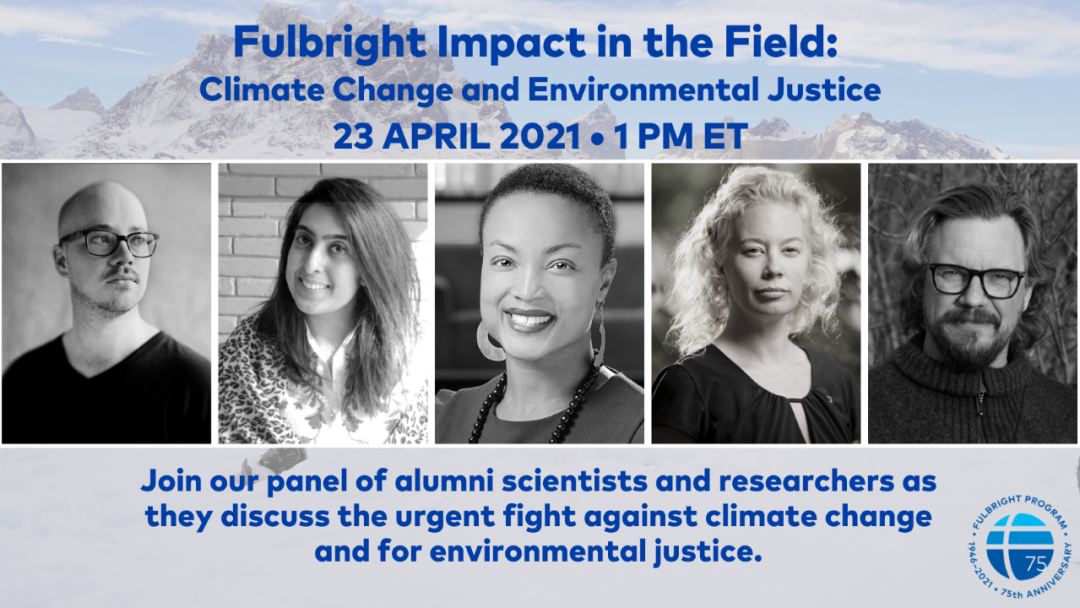

The Fulbright Impact in the Field: Climate Change and Environmental Justice panel convened scientists, researchers, and other professionals involved in combating climate change. They discussed the latest scientific and policy developments, and looked at how new approaches and international collaborations can be used to combat climate change and pursue environmental justice. These experts also shared their Fulbright experiences and the benefits of their new ideas at institutions and in communities.

Meet the Speakers

Moderator

Tim McDonnell (2016 Fulbright-National Geographic Storytelling Fellow to Kenya) is a climate and energy journalist at the global business magazine Quartz, covering the clean energy transition.

Panelists

Amber Ajani (2014 Fulbright Foreign Student from Pakistan to American University) is a Climate Fellow at the UN Climate Change secretariat and a recipient of the UNFCCC-UNU Early Career Climate Fellowship.

Shalanda Baker, JD (2016 Fulbright U.S. Scholar to Mexico) is the Deputy Director for Energy Justice in the Office of Economic Impact and Diversity at the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) and co-founder of Initiative for Energy Justice.

Dr. M Jackson (2011 Fulbright U.S. Student to Turkey, 2015 Fulbright U.S. Student to Iceland, 2018 Fulbright U.S. Scholar to Iceland) is a geographer, glaciologist, TED Fellow, Fulbright Alumni Ambassador, and National Geographic Society Explorer.

Dr. Greg Poelzer (2015 Fulbright Arctic Initiative Scholar, 2021 Fulbright Arctic Initiative Co-Lead Scholar) is a Professor in the School of Environment and Sustainability (SENS) and leads the Renewable Energy in Remote and Indigenous Communities Flagship Initiative at the University of Saskatchewan. He is also co-director of a multi-million-dollar Canadian Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) Partnership Grant.

Key Takeaways

1. We need to ensure that equity is central to our clean energy transition.

How can we ensure our infrastructure investment both reduces climate pollution and benefits marginalized communities?

This is a moment to think about how to “bake” equity into a new energy system, according to Deputy Director for Energy Justice Shalanda Baker. Her position underscores a commitment to address structural issues of energy use and environmental impact. The new Justice40 Initiative, which promises that 40% of relevant federal investment will benefit disadvantaged communities, ensures that every federal infrastructure investment accelerates clean energy and transmission projects in an environmentally sustainable manner.

Dr. Greg Poelzer, a Canadian expert on renewable energy in remote and Indigenous communities, and Co-Lead Scholar of the third Fulbright Arctic Initiative, urges us to focus on the opportunity that the energy transition provides for vulnerable Indigenous communities. He advocates for using strategic environmental assessments in systemic ecosystem review, and bringing in diverse voices for better long-term stability.

2. We need to make climate science communication more effective.

How can we communicate the core meaning of amazing scientific research, so that diverse communities can access it?

Glaciologist and explorer M Jackson uses mediums like film and art, rather than scientific journal articles, to visualize the impact of change. For example, her short film After Ice reveals the breathtaking story of a rapidly disappearing frozen world by overlaying archival imagery from the National Land Survey of Iceland with contemporary footage of glaciers in the South Coast of Iceland. This provides a dramatic look at how the ice has changed over the past 50 years.

3. We need to empower sustainable development decision-makers at the local level.

How do we ensure that policy implementation addresses capacity building and community issues?

Amber Ajani, a Fulbright Foreign Student from Pakistan to American University who now works at UN Climate Change, noted that it is important to include local stakeholders in strategic impact analysis and assessments. The panelists discussed that community “buy-in,” local stakeholder consultation, and the presence local communities in the “drivers’ seat” must come at the early stages of project development, rather than having ideas from the Global North applied to developing communities. For example, ideas that come out of Brussels, Ottawa, or Washington, D.C. to create eco-preserves could have negative impacts on the livelihoods of local Arctic communities. Shalanda Baker reminds us that today’s climate debate is not ahistorical: our current situation resulted from hundreds of years of the Global North exploiting natural resources for economic development at the expense of communities in the Global South. To create equitable climate policy, we need to understand and address this history.

To watch the panelists dive into these relevant discussions, click here.

The Fulbright Impact in the Field panel series is part of the Fulbright Program’s effort to help find solutions to challenges facing our communities and our world. Free and open to the public, this series provides a digital space for Fulbright alumni to share their expert perspectives and explore the program’s impact on local and global communities.

To learn about upcoming Fulbright 75th anniversary events, and see how you can get involved, sign up for the newsletter and visit Fulbright75.org.

Vince Redhouse, 2015 Fulbright U.S. Student in Philosophy to Australia

Vince Redhouse, 2015 Fulbright U.S. Student in Philosophy to Australia