Developing a strong, feasible and compelling project proposal is the most important aspect of a successful Fulbright application. Your first step should be to familiarize yourself with the program summary for the country to which you wish to apply. Program design varies somewhat from country to country (i.e., some countries encourage applicants to incorporate coursework into a project, while others prefer independent research). Click here to view the participating country summaries. Please ensure that your project design fits the program guidelines for your host country.

It is essential that applicants have adequate formal training for the study or research that they wish to pursue and that their language skills be commensurate with the requirements of their proposed project.

- Graduating seniors generally will be expected to attend regular university lectures as part of their projects. They should describe the study programs they wish to follow in very specific detail. They should not expect close academic supervision and should be prepared to supplement lectures with an independent research project.

- Graduate students, as well as advanced degree candidates proposing research for theses and dissertations, will be expected to work independently without close supervision.

- Ph.D. candidates should indicate when they expect to complete preliminary or comprehensive examinations and whether their project statements have been accepted as dissertation proposals.

- Creative and Performing Arts candidates should submit projects indicating their reasons for selecting a particular country, the form their work will take and the results they hope to obtain. For more information on preparing applications in these areas and any required supplementary materials, please click here.

Is the Project Feasible?

You must demonstrate that your project and your research strategy are feasible, including its time frame. In mapping out your project, ask yourself the following questions:

- How will the culture and politics of the host country impact my work?

- How do the resources of the host country support my project? Will I have access to the documents/equipment necessary for successful completion of the project?

- If employing such methodological techniques such as extensive interviewing and the use of questionnaires how will I get/locate subjects? Have I received approval for the questionnaire from the project supervisor?

- Do I have all of the necessary permissions from local authorities?

- Is my language ability adequate? If not, how will I accomplish my work? (Eligible applicants should also consider a Critical Language Enhancement Award for additional language training opportunities.)

In other words, if there could be any question regarding the feasibility of your project or your ability to conduct the project, address the issue directly. Enrolled students are urged to consult professors in their major fields and their Fulbright Program Advisers about the feasibility of their proposed projects; at-large applicants should consult qualified persons in their fields.

Master’s Degree Programs

Candidates considering earning a master’s degree must make sure that the country to which they are applying will accept their project. Some countries do not recommend that applicants apply to undertake a degree program for a number of reasons including the impossibility of completing a master’s degree in one academic year or the other Fulbright grant would not cover tuition fees charged. Applicants should review the country summaries to determine whether there are any restrictions in applying to complete a degree program. If you apply for a degree program in a country that does not offer tuition as part of the Fulbright funding package, then these costs must be covered from an alternative source.

If your plan is to complete a master’s or other structured degree program, make sure that you apply for admission to the host university by their deadline. Do not wait for the Fulbright decision to come through; it may be too late to gain admission to your preferred university.

A Brief Note on Host Affiliation

More information on establishing a host affiliation will be available in an upcoming newsletter. Please keep an eye out for this issue. If you are applying for admission to a university, it is not necessary to submit the letter of admission with the application (although this is desirable). You may submit the acceptance letter whenever you receive it, but an award offer would be contingent upon your placement at a university. If you are not planning to matriculate at a university, then a support/affiliation letter must be included with your application. Any support documentation you can obtain from a potential host will help to make your application more competitive and will also demonstrate the feasibility of your proposal.

English Teaching Assistantship (ETA) Applications

If you are applying as an ETA, you are not expected to present extensive research plans. Rather, you should describe the following to reviewers:

1. Why would you like to undertake a teaching assistant assignment?

2. What are your qualifications and what experiences do you have which relate to the overseas assignment?

3. How do you expect to benefit from the assignment and how will you use your experience upon returning to the U.S.?

4. What will you do outside the classroom (most ETAs work no more than 20 hours per week. See developing the statement of purpose for ETA grants on the website)?

All host country affiliations for ETAs will be arranged by the Fulbright supervising agency in the host country. ETA applicants should not attempt to arrange their own affiliations.

Writing the Study/Research Project Proposal

The best project proposals begin with good ideas. Start by putting your ideas on paper and listing your goals and objectives. Share your ideas with your Fulbright Program Adviser, your academic adviser and professional colleagues in your field. As you work on your project, consider the following questions, while remembering your audience. Avoid discipline-specific jargon. The individuals reading your proposal prefer that you be direct about the “who, what, when, where, why and how” of the project. In a persuasive manner, address the following:

1. With whom do you propose to work?

2. What do you propose to do? What is exciting, new or unique about your project? What contribution will the project make to the Fulbright Program’s goal of promoting cross-cultural interaction and mutual understanding?

3. When will you carry out your study or research? Include a timeline.

4. Where do you propose to conduct your study or research? Why is it important to go abroad to this specific country to carry out your project?

5. Why do you want to do this project? What is important or significant about it?

6. How will you carry out your work? All students should discuss methodology and goals in their statements.

7. How will this project help further your academic or professional development?

8. What will be the outcome of your study/research? (See Developing The Statement of Proposed Study or Research on the website)

A Bibliography

Since the Project Statement component of the Fulbright application cannot exceed two single-spaced pages, a formal bibliography is not necessary. However, if background data is provided, it is appropriate to briefly cite sources within the two pages.

Project Category for Applications in the Arts

Almost all creative/performing arts projects involve some kind of study or research as well as practical training. Therefore, you need to decide what the primary focus of your project is: academic research or a practical training in the arts. Keep in mind that creative/performing artists must also submit supplementary materials in addition to the written application. If you do not feel that your work to date in the arts is your best, it may be more appropriate to apply using an academic field of study, such as art history, theater studies, etc., in order to have your application reviewed appropriately.

Multi-Country Projects

A multi-country project is a project that must be carried out in more than one country. All countries must be within the same geographic world area. Applicants submitting multi-country proposals must have very good justification for putting forward such a project. Keep in mind that you are doubling or tripling the work involved in securing host institution affiliations, not to mention obtaining visas, finding housing, etc. Also, multi-country proposals recommended by screening committees must be approved by each of the relevant host countries before they can be granted. If one country rejects your project, then your project may not be feasible. Generally, you will be given the option of revising your proposal for the remaining countries which have approved your original project. Currently, multi-country proposals may only be submitted in the Western Hemisphere and in certain countries in Eastern Europe/Eurasia.

A Final Word…

Organize your statement carefully. Don’t make reviewers search for information. We urge you to develop a lead paragraph with all of the salient details – the who, what, when, where, why and how – and have several people read and critique your statement including a faculty adviser, a faculty member outside your discipline, a fellow student and/or a colleague. It would be ideal to have a host country academic or artist review your proposal for refinement and host country issues of sensitivity, security and feasibility.

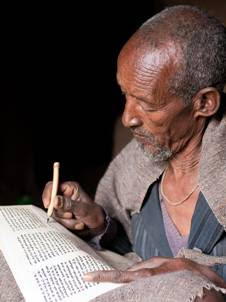

As a scholar of the development of book technology, I have spent a lot of time studying physical objects and wondering about the mindset craftsmen had while producing books in the Ancient and Medieval periods. Since the production of manuscript books in Europe died out centuries ago, it is impossible to ask the producers about their techniques. The tradition of manuscript production that exists (in a reduced state) in the Islamic world is different enough from the one practiced during historical Christendom to limit its utility for the study of traditional European bookmaking. That is why I was excited, during the course of my research, to discover that manuscript bookmaking still survives in the Christian highlands of Ethiopia; it was simply a matter of getting the time and funds to go.

As a scholar of the development of book technology, I have spent a lot of time studying physical objects and wondering about the mindset craftsmen had while producing books in the Ancient and Medieval periods. Since the production of manuscript books in Europe died out centuries ago, it is impossible to ask the producers about their techniques. The tradition of manuscript production that exists (in a reduced state) in the Islamic world is different enough from the one practiced during historical Christendom to limit its utility for the study of traditional European bookmaking. That is why I was excited, during the course of my research, to discover that manuscript bookmaking still survives in the Christian highlands of Ethiopia; it was simply a matter of getting the time and funds to go.