By Jeffrey Thiele, Fulbright U.S. Student Open Study/Research Grantee to El Salvador

As I reflect on my time as a 2018 Fulbright grantee to El Salvador, it might be easy to say that I accomplished my mission. I wanted to use my master’s degree in philosophy and health to solve a real-world problem: increasing healthcare access for Salvadorans displaced by violence by working with Cristosal, a local NGO. My grant year did give me plenty of opportunities to put theory into practice, but what I didn’t see coming, however, was the role that music would play in that journey.

When I arrived in San Salvador, I knew very little about the local political, economic, and social situation. I quickly realized that there are no quick fixes to the problems that El Salvador faces, and that I wouldn’t be able to make the sweeping changes I had anticipated going into my Fulbright. While I plugged away with the newfound perspective that I would be doing more learning than doing, another project began to occupy my nights.

This is where Saxo Sue, my loyal, traveling saxophone, appears. Having recently fallen back in love with music during my master’s program, Saxo Sue had made the voyage with me to San Salvador, though I had little hope of finding much music there. The first month of my time with Saxo Sue in–country was spent going over old classical repertoire in the light of the evening sun. While I was making occasional improvisations and recording them, I wasn’t really moving forward musically.

Two months in, one of my friends invited me to a gig where her friend’s boyfriend, a local trumpeter, would be playing with his group called The Zamora Brothers. I was so excited to learn that jazz was happening in the capital, and that there was such a vibrant music scene in a land where many people are still fighting for fundamental human rights. The concert got me thinking about the resilience of the arts and its unique ability to exemplify and push forward necessary human and social rights.

In the following weeks, Pipe (pronounced “pee-peh”), the trumpet player for the Zamora Brothers, invited me to a jam session at his house with another local band, Camelo. I connected with Camelo’s leader Jorge Gómez, who said Saxo Sue and I brought the final “oomph” and tonal character that the band was seeking. I was in.

Apart from joining Camelo as their seventh member, I became involved in about eight other music projects in and around San Salvador, including establishing my own jazz project, called Buxo Don Luis. Both Camelo and Buxo Don Luis have been getting national, and even international, recognition, and will be touring outside of El Salvador in the coming year.

My involvement and (unexpected) fame in the Salvadoran music scene has given me a wider-reaching platform from which I can share my thoughts and work on human rights and social justice. More broadly, music has been a means to not only express myself, but to advance a broader rights movement inside and outside the country. I participated in a “Reach the World” virtual exchange with a New Jersey elementary school classroom, where I balanced our conversations about heavy Salvadoran social issues with some improvisations with Saxo Sue. With music as the bridge, we accomplished a key Fulbright goal of building mutual understanding between cultures.

I came to El Salvador for research, and have come away pursuing my dream of becoming a bona fide musician. Music has helped me integrate into the community in San Salvador, empowered me to meet new people, and become an authentic participant in this beautiful culture. As I grow personally and professionally, I can share the joy of music and express the urgency of the situation in El Salvador.

The Fulbright Program is pleased to congratulate three alumnae on their selection as 2019 MacArthur Fellows! “Genius” Fellows Andrea Dutton (2020 U.S. Scholar to New Zealand), Saidiya Hartman (1997 U.S. Scholar to Ghana), and Stacy Jupiter (2002 U.S. Student to Australia) will each receive a $625,000, no-strings-attached award from the MacArthur Foundation to support their creative, intellectual, and professional projects.

According to the MacArthur Foundation’s website, fellowships are awarded to “talented individuals who have shown extraordinary originality and dedication in their creative pursuits and a marked capacity for self-direction.” It lays out the following criteria for the selection of Fellows:

- Exceptional creativity

- Promise for important future advances based on a track record of significant accomplishments

- Potential for the Fellowship to facilitate subsequent creative work.

Learn more about how each Fellow’s experience as a Fulbright participant supported and inspired their professional goals:

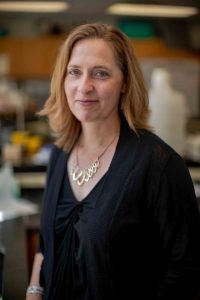

Andrea Dutton

Andrea Dutton: A University of Wisconsin-Madison geochemist and paleoclimatologist specializing in sea levels, Andrea Dutton will travel to New Zealand as a Fulbright U.S. Scholar in the spring of 2020. During her grant, she will analyze local coral and coastlines to better understand how sea levels are changing. Dr. Dutton is motivated to study and share her findings with people and communities specifically affected by rising seas.

Saidiya Hartman

Saidiya Hartman: A literary scholar and cultural historian, Saidiya Hartman “explores the limits of the archive” through telling the stories of African slaves, free black people, and other marginalized individuals excluded from the recent American past, and how those experiences inform the contemporary African American experience. During her nine months as a Fulbright U.S. Scholar to Accra, Ghana in 1997, Dr. Hartman studied the Atlantic slave trade through her project, entitled, “Belated Encounters on the Gold Coast: Captives, Mourners, and the Tragedy of Origins.” She has authored two books and is a professor of English and comparative literature at Columbia University.

Stacy Jupiter

Stacy Jupiter: A marine scientist, Stacy Jupiter works with indigenous Melanesian communities in Fiji, the Solomon Islands, and Papua New Guinea on ecosystem management by integrating local cultural practices with field research. Dr. Jupiter has collaborated on Fiji’s first “Ridge-to-Reef” management plan, which is currently used as a template for other areas in the region. During her Fulbright to Australia as a U.S. Student in 2002, she worked to contain and prevent microbial blooms in Moreton Bay, Queensland.

By Lindsey Liles, Fulbright English Teaching Assistant to Brazil

It’s nowhere near dawn, but Karina and I are already awake and dressed, standing outside the barn, laying out the traditional Gaucho tack we will use to saddle the horses. Karina’s horse, Cavalo de Fogo, pricks his ears and shifts his weight, sensing our excitement and no doubt wondering why he’s being fed his breakfast at three in the morning.

It’s the 21st of September, a special day in Porto Alegre, Brazil. For the whole month, Gauchos come from all over the state of Rio Grande do Sul to celebrate Semana Farroupilha, an event which commemorates the Farroupilha Revolution in 1835 and is a tribute to Gaucho culture and traditions. The Gauchos set up a temporary camp made of piquetes–open wooden structures that look like barns–and stay there for the month drinking chimarrao tea, grilling traditional Brazilian churrasco barbeque, and riding horses. The celebration culminates on the 21st, with a parade of hundreds of Gauchos in traditional dress through the city center. Through a little luck and a lot of work learning to ride sidesaddle over the past few months, I will be riding with them in the parade.

I am a Fulbright English Teaching Assistant here in Brazil, and signed up on a whim for a horseback ride with a local woman named Karina. Since that first ride, I have learned to ride with a traditional Gaucho saddle, bareback, and sidesaddle; joined a women’s Gaucha riding group; and made many friends in the Gaucho community. What started as a one-time activity has become a long-term project that has allowed me to study Gaucho culture while learning to ride among these traditional South American cowboys.

We arrive at another farm outside the city at 5:00 AM, and load the horses on a truck that will take them into the city center, and the parade. At the farm, it’s organized chaos–20 or so horses are tied out front and bundles of tack are everywhere. The other 18 riders in our group are all arriving too, dressed in bombachas, the wide billowing pants tucked into soft leather riding boots, crisp shirts, and the trademark wide and flat Gaucho hat.

Karina and I make small talk and check our horses. The horse I will ride, Helena, is a little restless. I give her a treat from the stash I brought along; I have learned the hard way that it’s in my best interest to keep her happy. I meet some of the other riders for the first time. “An American, riding with us!” they exclaim, and I explain that all I know of Gauchos, horses, and riding I know from my time here, and that it is an honor for me to ride among them. They welcome me with all the kindness and authenticity that I have experienced so many times since arriving in Brazil.

Once we arrive at the grounds of the parade, it’s time to saddle up. I carefully put on the riding skirt that Karina has lent me–her mother hand-sewed it for her 30 years ago, and it is meant to be ridden sidesaddle. Karina gives me a leg up, and I situate my right leg over the horn that secures a sidesaddle rider and let my left leg rest lightly on the stirrup. The idea is to look dainty and effortless; the reality is to hang on for dear life with the right leg hidden under the skirt. Karina arranges the folds of blue fabric so they sweep elegantly across Helena’s side. She looks at us, probably recalling the hours she spent teaching Helena and I to work together to keep me balanced in the saddle, and smiles. “Perfeito,” she pronounces, and I’m not sure if she is prouder of me or Helena. She mounts Cavalo de Fogo, and we are off.

As I ride Helena down the streets of Porto Alegre, surrounded by my Gaucho group and with Karina in front of me, I can’t help but think that more than anything, this is the heart of the Fulbright Program–finding common threads with people across cultures, languages, and ways of life. In my case, I share with the Gauchos the love of a gallop down a dirt road, a passed cup of chimarrao, and the open spaces of the countryside. The parade winds down past Guaiba Lake and towards the city center, and I look at the smiling faces of the people watching. I realize suddenly that they don’t know I am not Brazilian, and that it doesn’t matter. Today is about honoring Gaucho culture and celebrating a love of horses and a way of life that I have been fortunate enough to experience.

Written by Steven Tagle, Fulbright US Student to Greece 2016-17

At Mytikas, the highest peak of Mount Olympus, with Josh Arnold, an American friend I made on the way up

When I describe my year in Greece, I often feel like I’m describing a place I imagined rather than a place that actually exists. It is a place where golden light strikes marble columns and sparkles over the wine-dark sea; where rowdy, curious, and clever characters drink and dance; where tradition and innovation, creativity, and chaos brew in a social and economic cauldron. As a fiction writer with an admittedly tenuous grip on reality, I’ve inhabited Greece the way a reader inhabits a book. “Reading” Greece this year has reawakened my senses and bound me to Greek and Syrian people whose mythic stories have challenged what I thought I knew about the crises, and what I thought I knew about myself. I may be the newest reader of a book that spans millennia, but like Byron, Fermor, and Merrill, I’ve found a home in this country and hope to contribute to its pages.

The Vikos Gorge from the Beloi Lookout in Vradeto, supposedly the deepest gorge in Europe.

I came to Greece through its mythology, intrigued by a people whose gods were as raucous, petty, and vindictive as they were noble and just. The landscapes of Greece retain the mystery and power of mythology. Thanks to Fulbright, I’ve visited many of these places, where our world still seems to touch the world of the gods. I’ve walked along the Acheron River – the “River of Woe” – whose spectral blue waters seem colored by the spirits of the dead. I’ve listened for prophecy in the rustling oak leaves at Dodona and felt stalactites drip onto the back of my neck as a silent boatman ferried me through the caves at Diros. I’ve retraced Odysseus’s homeward path through the Ionian Islands and paid tribute to monsters Hercules had slain in the Peloponnese. Some days, traveling alone and outside my comfort zone, I walked on the edge of fear, knowing that beyond fear is awe, or δέος, the proper attitude for approaching the gods.

I saw δέος on a Naoussan boy’s face during Carnival when he put on the wax mask of the γενίτσαρος for the very first time. I learned to play Trex in UNHCR hotels and befriended an amorous Iraqi who had lost his legs as a child. My students at Aristotle University of Thessaloniki shared their yiayias’ spoon sweets and their own stories of first love, of coming out, of overcoming anxiety, of living with HIV. I visited their hometowns, stations of my Syrian friends’ wayward journeys. I know which cheeses each island produces and for which dessert each village is famous. Everyone I’ve met breathes a bit of Greece into me, and their life stories take root in my imagination. Now initiated into Greek culture, I’m eager to soak up every bit of history and myth, new local food, new tradition.

At Kallimarmaro Stadium with the Solidarity Now team, the first refugee team to run in the Athens Marathon.

A monk on Mount Athos gave me this advice: To write distinctly, live distinctly. In Greece I learned a different way to live. I’ve always held myself apart from people, but here, I was expected to spill into other people’s lives, to reach over them for food, to let myself need and be needed by them. Friends who have visited me in Greece say that I speak louder in Greek, that I’m more willing to talk to strangers, more willing to ask for help. They notice how Greek people open up to me when I speak the language. When a Greek asks me if I’m part Greek, I respond, Ναι, η καρδιά μου είναι ελληνική, “Yes, my heart is Greek.” Completing my Fulbright year is a bittersweet accomplishment, like coming to the of a beloved book. But as Greece has become part of me, so has my experience become part of the story of Greece.

By Niecea Freeman, Fulbright ETA to Czech Republic 2018-2019

“How about: It’s quality, not quantity?” my dad proposed, wearing a grin. We were brainstorming city slogans for Loyalton, California, my hometown of 800 people nestled in the Sierra Nevada mountains—now named “the Loneliest Town in America.” We all laughed. On the surface, country living seems like paradise, but in reality a myriad of issues affect rural communities across the nation. Employment opportunities are sparse, lower income leads to higher instances of poverty, and—consequently—there is a clear demand and absolute need for higher quality education.

When the town’s sawmill closed in 2001, followed by a mass population exodus, Loyalton’s tax revenues declined rapidly and ancillary school programming disappeared with them. First, we lost music and art specials. Later, our middle school was condemned, and students were moved from portable buildings into the high school, losing their separate facilities entirely. In truth, it has only been through the extraordinary efforts of dedicated teachers and community members that our school district has been kept afloat: teachers like my high school Spanish instructor, Megan Meschery, who are determined to redefine our local community without much funding from state or federal agencies.

In 2008, Megan left for a Fulbright grant in Granada, Spain, where she examined how rural economic development funding provided by the European Union reduced inequalities in public schools regardless of geographic location. She sought to find parallels and lessons applicable to rural education in America and to develop ways to promote cultural awareness and growth in Loyalton. While Megan’s experiences rather highlighted the differences between U.S. and EU development models, Megan also returned from her two-year Fulbright burgeoning with ideas tailored to Loyalton’s situation, and immediately found ways to introduce positive change, starting with school electives.

My favorite memories from high school are from the culture club she initiated, through which I saw my first Broadway play, Wicked, and visited my first classical art exhibit, featuring masterpieces from Rembrandt and Raphael. These experiences opened my eyes to the world beyond our tiny valley, and change did not stop there.

The following year, Megan founded a non-profit organization called The Sierra Schools Foundation (SSF – sierraschoolsfoundation.org) to combat inequality in the school district by providing grants for resources and programs such as the STEM Learning Garden, Local-Artists-in-the-School, Advancing to College SAT prep, and others. I volunteered with SSF throughout college, running fundraisers, where I witnessed firsthand how, with dedication and perseverance, local organizations genuinely have power to initiate positive change.

These formative experiences propelled me to apply for a Fulbright English Teaching Assistantship in the Czech Republic for the 2018-2019 academic year, where I will be living in a rural community not unlike Loyalton, teaching English to secondary students enrolled in veterinary and agricultural programs. As an undergrad, I pursued a B.S. in Integrated Elementary Education with an emphasis in English as a Second Language with the primary goal of becoming an elementary school teacher in a high-needs, rural community in the United States. Now, I am ready to go forward and learn from the students and families of my host country to explore new perspectives and pedagogies that will reshape the way I view myself and my role as an educator. The quantity of programs in Loyalton’s schools has stagnated, but the quality of our education can continue to blossom