This National Hispanic Heritage Month, we’re highlighting the contributions of outstanding Fulbrighters who live the Fulbright mission through their identities and goals. In this Q&A, Fulbright Student Alumni Ambassadors Tania Aparicio, Maren Lujan, and Abraham De La Rosa share their experiences and discuss inclusion and equity in international education, especially as it relates to their own experiences and identities.

Tania Aparicio, 2018 Fulbright U.S. Student in Sociology and Film to Mexico

In Mexico, Tania conducted qualitative research for her doctoral dissertation, which focuses on the decision-making process involved in film curatorship. Her doctoral thesis proposes that curatorship is a collective process influenced by the principles that organizations stand for and not based on individual taste, as other scholars have previously claimed. Working with the curatorial team at the Cineteca Nacional de Mexico, Tania conducted participant observation on how film curators make and justify programmatic decisions.

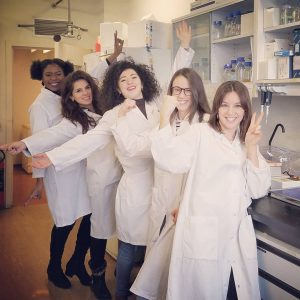

Abraham M. De La Rosa, 2018 Fulbright U.S. Student in Public Administration to Italy

Abraham earned a master’s degree in Public Administration through the SDA Bocconi School of Management in Milan, Italy, where he studied how the public and private sectors can collaborate to tackle new challenges across the globe. As part of this program, he interned with Officine Innovazione-Deloitte Italy and Rise Products to conduct market research on the global flour industry and upcycling products. In addition to his coursework, Abraham worked on a capstone research project focused on social impact bonds for refugees in the European Union, which he presented at the European Investment Bank in Luxemburg.

Maren A. Lujan, 2017 Fulbright U.S. Student in Anthropology to Sierra Leone

Maren’s Fulbright research focused on studying social and cultural structures impacting women’s access to healthcare. While in Sierra Leone, Maren conducted ethnographic research in a rural town, as well as system analysis at the regional and national levels. She worked with a Sierra Leonean research assistant and collaborated with a non-governmental organization, FOCUS 1000, to employ participatory research techniques at the local level.

1. Tell us a little about your path to Fulbright. Who or what inspired you to apply?

Tania: Fulbright is one of the most prestigious grants for graduate students. I had looked into programs to fund research in Mexico, and found my doctoral dissertation project, which is arts-based, was a good fit for the Fulbright Open Study/Research Award to Mexico. When I started my application in early May, I attended an informational session at my university. There, I met Katie Wolff, Assistant Director of Global Engagement & International Programs, and The New School’s Fulbright Program Adviser. She met with me and helped me set up a timeline to get my application materials completed during the summer. I could not have done it without her.

Abraham: I had known about Fulbright for a couple of years, but I had the misconception that Fulbright was for STEM students to continue undergraduate research projects. It was not until a few years ago that I discovered that there are a lot of different Fulbright awards available across the world. While I was working full time, I discovered that you could pursue a master’s program through Fulbright. I found an award that aligned with my educational and professional background, as well as what I wanted to continue to learn, and I decided to apply. The process was quite hectic, especially since I was working. Luckily, I had the support of my supervisor and roommate, who made sure I stayed with my application and submitted.

Maren: I don’t recall exactly what prompted me to apply. I wasn’t even entirely sure what Fulbright was before applying. A friend of mine had completed a program through Fulbright, so I was familiar with the name; perhaps a professor mentioned it offhand as an option. I applied, got it, and then figured it out from there!

2. Tell us a little about your Fulbright research topic and project. What did a typical day as a Fulbrighter look like for you?

Tania: I spent nine months in Mexico City gathering qualitative data for my doctoral dissertation, which investigates film curatorship in two important arts organizations. I wanted to understand how curatorial decisions are made, because they impact the film culture that millions of people have access to. My first case was the Museum of Modern Art in New York City and the second was Cineteca Nacional (The National Film Center) in Mexico City.

Caption: Tania Aparicio on her Fulbright, posing in front of her host institution, Cineteca Nacional in Mexico City, Mexico.

As a Fulbrighter, I conducted participant observation as a member of the Programming Department with Cineteca Nacional. I spent most of my time with the head curators, who decide what films 1.3 million annual visitors will watch in the film center. I was lucky to attend private film screenings and observed their firsthand reactions to the films they were judging, how they classified them, and the type of evaluation processes they engaged in. I also shadowed each member of the department, including theater managers, shipping employees, film rights managers, assistants, and interns. During the last three months of my stay, I conducted in-depth interviews with film curators who worked for other organizations, as well as other important industry members, in order to get a fuller idea of the field and of how Cineteca Nacional fit in the larger cultural landscape in Mexico. I also conducted workshops for local graduate students on how to conduct qualitative research when studying forms of cultural production, such as cinema.

Abraham: My Fulbright allowed me to pursue a Master of Public Administration degree (MPA) through the SDA Bocconi School of Management in Milan, Italy. I primarily attended classes as a graduate student and my typical day really varied. My first semester focused on courses and content, while during the second semester, I worked with classmates on a research project focused on public-private partnerships and social impact bonds for refugees in Europe. After completing the research project towards the end of the semester, I completed coursework while interning with a consulting company.

In addition, I volunteered in the local community and went hiking out of the city during the weekend. It’s hard to describe a typical day, since it really changed depending on the month and where I stood in my program.

Maren: My research topic looked at women’s health in rural Sierra Leone from a social and cultural perspective. A typical day for me was walking around the rural town where I was staying, or visiting one of the many surrounding villages, and talking with individuals about their health and their experiences with the health system.

Abraham De La Rosa at the United Nations Office at Geneva during a multi-day excursion in Switzerland, as part of his master’s degree program.

3. How did your identity play a role in your Fulbright experience?

Tania: I often had conversations about how, as an immigrant from Peru, I am from “here and there,” to borrow a phrase from Alexandra Delano, the Co-Chair and Associate Professor of Global Studies at The New School, who has written about diaspora policies, integration, and social rights beyond borders. In my experience, I received pushback from people who wanted to label me exclusively as Peruvian, rather than Peruvian-American. Nevertheless, I do not think of myself only as Peruvian anymore, and I haven’t for a long time, even though I moved to the United States as an adult and without my family. I am grateful for the opportunity I had to reflect and discuss my identity as an immigrant with my peers in Mexico. I came to realize how formative my immigration trajectory has been, and how I could never be who I’ve become anywhere else but in the United States.

Abraham: My identity played a big role in my Fulbright experience, since my courses were discussion-based. One of the topics we kept going back to was how governments and the private sector can better serve their communities. During these discussions, I was able to share with my classmates my Mexican and American experience in the United States. For most of them, it was their first time interacting with an immigrant and first-generation college student. Being able to have these deep conversations with my classmates and members of the community allowed me to share a side of the United States not normally shown in mainstream media.

Maren: Being light-skinned in Sierra Leone and West Africa categorizes you as “apotho” (white/foreigner), and with that comes privilege and certain expectations, especially in rural areas. Residents’ experiences with foreigners is commonly through foreign aid: when I approached people to talk about their health, I was assumed to be a doctor, and very often get asked for medical advice and medicine. This was also part of my research on the health system: considering the impact of international aid. A few distrusted my intentions, so a lot of my work was also building trust.

Additionally, being American, there were often assumptions of wealth—I did want individuals to understand that there is also poverty, racism, and inequality in the United States. As a first-generation Mexican-American, it felt important to me to share my experiences, but navigating those conversations could be difficult given the disparities and differences in access, and given that poverty in the United States looks very different from poverty in rural Sierra Leone.

Abraham De La Rosa participating at the Seeds&Chips Summit through his internship in Milan, Italy.

4. What is your biggest takeaway from your Fulbright?

Tania: Where, what, and how a new place becomes home is always unexpected. Also, every Fulbrighter I’ve met since my grant started are members of this amazing community of kind and insightful human beings.

Caption: Tania Aparicio visiting Palenque archeological site in Mexico.

Abraham: One of the biggest takeaways from my Fulbright is realizing that we have a lot in common with others around the world. My master’s program was composed of people from 16 different countries, and I was surprised constantly by how our countries worked similarly to try to help our communities. I found myself sometimes realizing that what I understood about a country or situation from a U.S-based perspective was not the full story. Through trying to learn mutually from others, I was able to also see a different reality about their countries and societies. These are skills that I found extremely helpful, and that I continue to use even upon my return to the United States.

Maren: Being a first-generation college graduate, I’m still amazed that programs like Fulbright exist. The fact that I was given the opportunity and funding to pursue my own research is still unbelievable to me. This has set me up for a PhD. While I will need to continue to pursue funding for my research, I do feel a sense of confidence now in seeing that my work has value, and that someone was willing to fund it.

5. What impact did your research or studies make in your career and local communities?

Tania: I could not have completed my dissertation research without Fulbright. Due to this research, I have presented in conferences in both Mexico and the United States, prepared articles for publication in peer-reviewed journals, and I’m currently writing my PhD dissertation. My work is a comparative study of film curatorship in a U.S.-based non-profit and a Mexico-based public organization—this comparative approach is yielding new knowledge for cultural managers and practitioners.

Abraham: My Fulbright allowed me to continue to advance professionally. Since my return to the United States, I have been working with a non-profit organization, The Forum on Education Abroad, applying a lot of my acquired knowledge. The organization works directly with universities and study abroad providers to ensure best practices in the field of education abroad.

Maren: My research focused on the use of participatory practices: how to engage with community while conducting research, and considering the impact of that research on them. I currently facilitate a community health plan with a variety of health service providers and engage with stakeholders to maximize impact. I’ve been able to re-focus the work to community impact and implement strategies for engaging with residents, folding health equity into the action plan.

Abraham De La Rosa with two classmates at La Scala Opera House in Milan, Italy.

6. What does equity and inclusion look like in international education/study abroad?

Tania: It looks like networks of people helping each other move up and forward together. For example, it looks like first-generation college students learning about programs like Fulbright and getting the mentorship and support to navigate the application process.

Tania Aparicio touring Mexico City with fellow Fulbrighter.

Abraham: This is a very complex question and I think many in the field of international education are trying to answer this. Equity, diversity, and inclusion are guiding principles that should be embedded in every aspect of international education, and considered prior to a program even beginning. When a program or an opportunity abroad is being designed, underserved and unrepresented populations should be kept in mind throughout the entire design process. This includes, but is not limited to, the mission and goals of the program; the populations for whom the program is intended; the application process; financial assistance; and the support that will be provided to each participant before, during, and after their experience abroad. If underserved and unrepresented participants are not kept in mind from the very beginning, trying to ensure equity and inclusion at the end of the process will be much more difficult and perhaps ineffective.

In a broader sense, we hope that everyone can participate in international education, and that each participating cohort is representative of the vast diversity of the United States. The goal is an opportunity where everyone feels welcomed and equally served, regardless of gender, race, identity, or background, and where you can feel safe sharing who you are and learn from others. I think the field of international education continues to improve and grow, but we can all continue to learn and share with one another to continue to grow.

Maren: I think when discussing equity and inclusion for study abroad, we want to look at the students who have historically been disenfranchised or wouldn’t have access otherwise. Recently, someone mentioned that study abroad demographics mirrored higher education numbers. If you consider all the barriers to education for low-income, minority, disabled students, and others, we have to ask: are we maximizing equity, or maintaining a status quo where only the elites and outliers have access to study abroad and international education? I got lucky learning about Fulbright and was given the opportunity of a lifetime, but I know in that respect, I’m still an outlier.

Abraham De La Rosa hiking in Lecco, Italy, located 30 km outside of Milan.

Vince Redhouse, 2015 Fulbright U.S. Student in Philosophy to Australia

Vince Redhouse, 2015 Fulbright U.S. Student in Philosophy to Australia