Most people have the same image of all primates. This generic ape or monkey swings through the trees, eats bananas and lives in a small social group of about 20-30 individuals. Few people imagine monkeys that sleep on sheer cliffs. Even fewer folks think a primate could eat grass. And only a handful of people have ever observed over 1,000 wild primates living together in a single social group. Through my Fulbright grant, I had the fortune of spending time with a peculiar primate species that exhibits all three of these behaviors. During a 10-month stay in Ethiopia, I studied the behavior of geladas (Theropithecus gelada).

Most people have the same image of all primates. This generic ape or monkey swings through the trees, eats bananas and lives in a small social group of about 20-30 individuals. Few people imagine monkeys that sleep on sheer cliffs. Even fewer folks think a primate could eat grass. And only a handful of people have ever observed over 1,000 wild primates living together in a single social group. Through my Fulbright grant, I had the fortune of spending time with a peculiar primate species that exhibits all three of these behaviors. During a 10-month stay in Ethiopia, I studied the behavior of geladas (Theropithecus gelada).

Geladas are known by their nickname, the “bleeding heart baboon.” Geladas are not, however, true baboons. While baboons eat meat, fruit, and nuts, geladas are the only primate species to feed nearly entirely on grass (over 90% of their diet). Their “bleeding heart baboon” nickname comes from the unique bare patch of skin located on the chest and neck of both male and female geladas. In females, this patch changes color from light pink to deep red with beaded vesicles and is thought to be a visual indicator of estrous. The male chest patch is likely a sexually selected signal, as chest color varies across males and is associated with dominance status.

My Fulbright grant allowed me to conduct dissertation research on the social and hormonal factors that influence bachelor geladas’ behavior living in all-male groups. In these groups, males may form bonds with other males that may persist through adult life. Young bachelors are often smaller than dominant leader males and may cooperate to overthrow leaders in order to mate with females. My research examines the nature of these relationships, particularly if young males are more likely to cooperate with their buddies when fighting leader males. Additionally, I collected feces to understand stress hormone level variation among bachelor males. These data will allow me to understand the relationship between stress and social bonding among male geladas, and is important for an understanding of how human friendships evolved.

While geladas may have been the primate of interest for my thesis, they were not the only primates involved in my Fulbright experience. I worked closely with many humans as well during my time in Ethiopia. Since I worked at Simien Mountains National Park (a UNESCO World Heritage Site), I lived with the park scouts and their families. I worked with a field assistant, Esheti Jejaw, and trained him in various scientific methods. In turn, he taught me how to speak Amharic, make injera (traditional Ethiopian bread), and navigate the cliffs of the Simien Mountains. Finally, my relationship with the U.S. Embassy in Addis Ababa allowed me to speak to high school students about my research and conserving Ethiopian biodiversity. I hope that at least one of these students pursues a future in wildlife biology, but I’ll settle for eco-minded doctors, lawyers, and future leaders of Ethiopia.

- If you are interested in applying for a Fulbright study/research grant, I recommend you always be mindful of the Fulbright Program’s mission to promote mutual understanding between the U.S. and the people of other countries. Find creative ways to incorporate this into your research plan, even if you study plants, birds, or primates. You should be foremost an intellectual ambassador, and secondarily, a researcher.

- If you are currently at a university, seek out faculty members that have had Fulbright experiences. Get to know them and ask them for reference letters. Do not think, however, that having a recommendation from a Fulbright alumnus guarantees a grant. It is far more important to have recommenders that know you both personally and academically.

- Finally, your research proposal should be something that can be accomplished within an academic year. Think of it as the first step to a larger project that incorporates the Fulbright Program’s goals. You cannot cure diseases or save entire ecosystems in less than a year, but you can make significant progress and impact lives that will last well beyond your grant tenure.

Top photo: David Joseph Pappano, 2010-2011, Ethiopia (left), with his field assistant, Esheti Jejaw

David Joseph Pappano, 2010-2011, Ethiopia, speaking to high school students about his Fulbright research at the “Yes Youth Can!” conference held at the U.S. Embassy in Addis Ababa on April 30, 2011

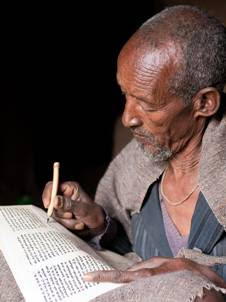

A male gelada looks out over the Simien Mountains, Ethiopia