Giffin Daughtridge, 2011-2012, Colombia, and fellow 2011 Fulbright U.S. Student to Colombia Emma Din at Monserrate, a chapel overlooking all of Bogotá, during their orientation week.

Francesca and I were both 22 when we first met in 2011. She was a transsexual sex worker, and I was doing street outreach with the Fundación Fénix as part of my Fulbright U.S. Student grant to Bogotá, Colombia. Through our conversation, I learned she had undergone multiple surgeries from unlicensed street side providers to augment various parts of her body, consistently used a range of drugs, and engaged in sex work with up to 12 clients per day.

I enjoyed our conversation, but it also left me frustrated. Francesca was at extremely high risk of contracting an infectious disease like Hepatitis B (HBV), but she was also at extremely low likelihood of having access to the HBV vaccine. She was deeply distrustful of the public system stemming from years of abuse from police and stigma from healthcare providers, and she refused to go to any clinic or hospital to get the vaccine.

As a result, I dedicated my year to delivering Hepatitis B vaccines to the populations at highest risk of contracting the disease. In Bogotá, this was the female and transsexual sex worker population. By leveraging the healthcare resources of the Bogotá Secretary of Health and the community network with the sex worker population of the Fundación Fénix, we administered HBV vaccines to almost 200 high-risk individuals in their work places.

The Fulbright Program launched a new passion for me. My academic studies at the Universidad Nacional gave me a foundation in public health and epidemiology while the flexibility of the grant allowed me exposure to the issue of limited vaccination coverage and the ability to pursue my solution. My biggest piece of advice to future Fulbright U.S. Students is to take full advantage of the flexibility of the grant to find and address a pressing need in your host country. Be adventurous in connecting with groups and people working in your interest area, and then allow your original project proposal to evolve to meet the issues that oftentimes you only find once you are in your host country. Pursue your solution during your Fulbright year, and then allow that project to come home with you and explore opportunities to continue your work in the United States.

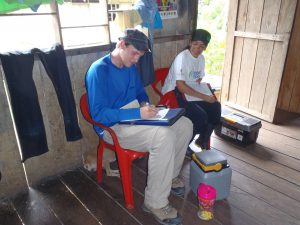

Giffin Daughtridge, 2011-2012, Colombia, working to deliver Hepatitis B vaccines outside of Leticia in the Amazon

For me, I knew that Francesca’s story was not limited to Bogotá. The populations at highest risk of infectious disease are often those least likely to have access to the medications that can protect them from that disease. When I returned to the United States after my Fulbright year and began medical school in Philadelphia, I wanted to continue the work I had done in Bogotá. While the U.S. has been more comprehensive in vaccinating against HBV, HIV remains an expensive and prevalent issue. 50,000 Americans are infected with HIV annually, and the U.S. spends $25 Billion just domestically on the disease every year.

Like HBV, though, there is a way to prevent it. PrEP is a medication that is 99% effective at preventing HIV in non-infected individuals if it is taken daily. Unsurprisingly, the populations at highest risk of HIV infection have the most barriers to receiving it and taking it adherently. These barriers include but are not limited to poor financial resources, lack of medical insurance, poor access to a healthcare provider, and stigma against taking a drug like PrEP, which is associated with HIV and its risk factors.

To overcome these obstacles, in 2013, I partnered with Dr. Helen Koenig, who was just starting an HIV prevention clinic in Philadelphia aimed at using adherent PrEP in high-risk young, gay patients to prevent HIV infections.

Today, that clinic provides PrEP on a consistent basis to almost 150 patients in Philadelphia and has served as a model for similar programs that are being started across the country.

Giffin Daughtridge, 2011-2012, Colombia, working with an epidemiologist from his academic affiliate, the Universidad Nacional in Bogotá, to deliver Hepatitis B vaccines in the Amazon.

While gaining access to PrEP for this population helps, it is only half the journey. PrEP is not a vaccine, and adherence is critical. To improve adherence, Helen and I founded an HIV prevention company called UrSure. We make patient friendly urine tests that let doctors measure their patients’ adherence to PrEP. Our tests are painless and noninvasive, cheaper, and deliver rapid results, which are a huge advantage for both patients and doctors over the alternative blood and pubic hair tests. Chris, who is one of the patients in our clinic, described how empowering he felt upon seeing his PrEP urine test results: “For the first time in my life, I knew I was protected from HIV.”

After winning the Harvard Business School’s New Venture Competition on the Social Enterprise Track, UrSure now has the resources to continue improving and scaling our urine tests both domestically and internationally. I look forward to taking this intervention to Bogotá, Colombia and talking to Francesca about preventing HIV, which could now be as easy as one, two, pee.

No Comments