By Jeffrey Thiele, Fulbright U.S. Student Open Study/Research Grantee to El Salvador

As I reflect on my time as a 2018 Fulbright grantee to El Salvador, it might be easy to say that I accomplished my mission. I wanted to use my master’s degree in philosophy and health to solve a real-world problem: increasing healthcare access for Salvadorans displaced by violence by working with Cristosal, a local NGO. My grant year did give me plenty of opportunities to put theory into practice, but what I didn’t see coming, however, was the role that music would play in that journey.

When I arrived in San Salvador, I knew very little about the local political, economic, and social situation. I quickly realized that there are no quick fixes to the problems that El Salvador faces, and that I wouldn’t be able to make the sweeping changes I had anticipated going into my Fulbright. While I plugged away with the newfound perspective that I would be doing more learning than doing, another project began to occupy my nights.

This is where Saxo Sue, my loyal, traveling saxophone, appears. Having recently fallen back in love with music during my master’s program, Saxo Sue had made the voyage with me to San Salvador, though I had little hope of finding much music there. The first month of my time with Saxo Sue in–country was spent going over old classical repertoire in the light of the evening sun. While I was making occasional improvisations and recording them, I wasn’t really moving forward musically.

Two months in, one of my friends invited me to a gig where her friend’s boyfriend, a local trumpeter, would be playing with his group called The Zamora Brothers. I was so excited to learn that jazz was happening in the capital, and that there was such a vibrant music scene in a land where many people are still fighting for fundamental human rights. The concert got me thinking about the resilience of the arts and its unique ability to exemplify and push forward necessary human and social rights.

In the following weeks, Pipe (pronounced “pee-peh”), the trumpet player for the Zamora Brothers, invited me to a jam session at his house with another local band, Camelo. I connected with Camelo’s leader Jorge Gómez, who said Saxo Sue and I brought the final “oomph” and tonal character that the band was seeking. I was in.

Apart from joining Camelo as their seventh member, I became involved in about eight other music projects in and around San Salvador, including establishing my own jazz project, called Buxo Don Luis. Both Camelo and Buxo Don Luis have been getting national, and even international, recognition, and will be touring outside of El Salvador in the coming year.

My involvement and (unexpected) fame in the Salvadoran music scene has given me a wider-reaching platform from which I can share my thoughts and work on human rights and social justice. More broadly, music has been a means to not only express myself, but to advance a broader rights movement inside and outside the country. I participated in a “Reach the World” virtual exchange with a New Jersey elementary school classroom, where I balanced our conversations about heavy Salvadoran social issues with some improvisations with Saxo Sue. With music as the bridge, we accomplished a key Fulbright goal of building mutual understanding between cultures.

I came to El Salvador for research, and have come away pursuing my dream of becoming a bona fide musician. Music has helped me integrate into the community in San Salvador, empowered me to meet new people, and become an authentic participant in this beautiful culture. As I grow personally and professionally, I can share the joy of music and express the urgency of the situation in El Salvador.

The Fulbright Program is pleased to congratulate three alumnae on their selection as 2019 MacArthur Fellows! “Genius” Fellows Andrea Dutton (2020 U.S. Scholar to New Zealand), Saidiya Hartman (1997 U.S. Scholar to Ghana), and Stacy Jupiter (2002 U.S. Student to Australia) will each receive a $625,000, no-strings-attached award from the MacArthur Foundation to support their creative, intellectual, and professional projects.

According to the MacArthur Foundation’s website, fellowships are awarded to “talented individuals who have shown extraordinary originality and dedication in their creative pursuits and a marked capacity for self-direction.” It lays out the following criteria for the selection of Fellows:

- Exceptional creativity

- Promise for important future advances based on a track record of significant accomplishments

- Potential for the Fellowship to facilitate subsequent creative work.

Learn more about how each Fellow’s experience as a Fulbright participant supported and inspired their professional goals:

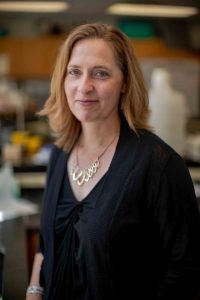

Andrea Dutton

Andrea Dutton: A University of Wisconsin-Madison geochemist and paleoclimatologist specializing in sea levels, Andrea Dutton will travel to New Zealand as a Fulbright U.S. Scholar in the spring of 2020. During her grant, she will analyze local coral and coastlines to better understand how sea levels are changing. Dr. Dutton is motivated to study and share her findings with people and communities specifically affected by rising seas.

Saidiya Hartman

Saidiya Hartman: A literary scholar and cultural historian, Saidiya Hartman “explores the limits of the archive” through telling the stories of African slaves, free black people, and other marginalized individuals excluded from the recent American past, and how those experiences inform the contemporary African American experience. During her nine months as a Fulbright U.S. Scholar to Accra, Ghana in 1997, Dr. Hartman studied the Atlantic slave trade through her project, entitled, “Belated Encounters on the Gold Coast: Captives, Mourners, and the Tragedy of Origins.” She has authored two books and is a professor of English and comparative literature at Columbia University.

Stacy Jupiter

Stacy Jupiter: A marine scientist, Stacy Jupiter works with indigenous Melanesian communities in Fiji, the Solomon Islands, and Papua New Guinea on ecosystem management by integrating local cultural practices with field research. Dr. Jupiter has collaborated on Fiji’s first “Ridge-to-Reef” management plan, which is currently used as a template for other areas in the region. During her Fulbright to Australia as a U.S. Student in 2002, she worked to contain and prevent microbial blooms in Moreton Bay, Queensland.

By Lindsey Liles, Fulbright English Teaching Assistant to Brazil

It’s nowhere near dawn, but Karina and I are already awake and dressed, standing outside the barn, laying out the traditional Gaucho tack we will use to saddle the horses. Karina’s horse, Cavalo de Fogo, pricks his ears and shifts his weight, sensing our excitement and no doubt wondering why he’s being fed his breakfast at three in the morning.

It’s the 21st of September, a special day in Porto Alegre, Brazil. For the whole month, Gauchos come from all over the state of Rio Grande do Sul to celebrate Semana Farroupilha, an event which commemorates the Farroupilha Revolution in 1835 and is a tribute to Gaucho culture and traditions. The Gauchos set up a temporary camp made of piquetes–open wooden structures that look like barns–and stay there for the month drinking chimarrao tea, grilling traditional Brazilian churrasco barbeque, and riding horses. The celebration culminates on the 21st, with a parade of hundreds of Gauchos in traditional dress through the city center. Through a little luck and a lot of work learning to ride sidesaddle over the past few months, I will be riding with them in the parade.

I am a Fulbright English Teaching Assistant here in Brazil, and signed up on a whim for a horseback ride with a local woman named Karina. Since that first ride, I have learned to ride with a traditional Gaucho saddle, bareback, and sidesaddle; joined a women’s Gaucha riding group; and made many friends in the Gaucho community. What started as a one-time activity has become a long-term project that has allowed me to study Gaucho culture while learning to ride among these traditional South American cowboys.

We arrive at another farm outside the city at 5:00 AM, and load the horses on a truck that will take them into the city center, and the parade. At the farm, it’s organized chaos–20 or so horses are tied out front and bundles of tack are everywhere. The other 18 riders in our group are all arriving too, dressed in bombachas, the wide billowing pants tucked into soft leather riding boots, crisp shirts, and the trademark wide and flat Gaucho hat.

Karina and I make small talk and check our horses. The horse I will ride, Helena, is a little restless. I give her a treat from the stash I brought along; I have learned the hard way that it’s in my best interest to keep her happy. I meet some of the other riders for the first time. “An American, riding with us!” they exclaim, and I explain that all I know of Gauchos, horses, and riding I know from my time here, and that it is an honor for me to ride among them. They welcome me with all the kindness and authenticity that I have experienced so many times since arriving in Brazil.

Once we arrive at the grounds of the parade, it’s time to saddle up. I carefully put on the riding skirt that Karina has lent me–her mother hand-sewed it for her 30 years ago, and it is meant to be ridden sidesaddle. Karina gives me a leg up, and I situate my right leg over the horn that secures a sidesaddle rider and let my left leg rest lightly on the stirrup. The idea is to look dainty and effortless; the reality is to hang on for dear life with the right leg hidden under the skirt. Karina arranges the folds of blue fabric so they sweep elegantly across Helena’s side. She looks at us, probably recalling the hours she spent teaching Helena and I to work together to keep me balanced in the saddle, and smiles. “Perfeito,” she pronounces, and I’m not sure if she is prouder of me or Helena. She mounts Cavalo de Fogo, and we are off.

As I ride Helena down the streets of Porto Alegre, surrounded by my Gaucho group and with Karina in front of me, I can’t help but think that more than anything, this is the heart of the Fulbright Program–finding common threads with people across cultures, languages, and ways of life. In my case, I share with the Gauchos the love of a gallop down a dirt road, a passed cup of chimarrao, and the open spaces of the countryside. The parade winds down past Guaiba Lake and towards the city center, and I look at the smiling faces of the people watching. I realize suddenly that they don’t know I am not Brazilian, and that it doesn’t matter. Today is about honoring Gaucho culture and celebrating a love of horses and a way of life that I have been fortunate enough to experience.

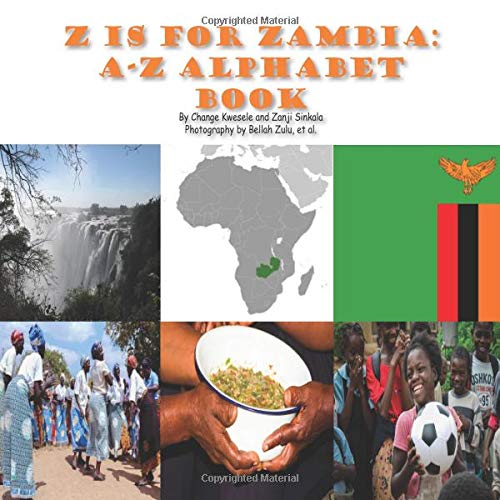

Many Fulbrighters return home with fresh ideas for research projects and international collaborations. For Change Kwesele, it was no different. Her goal? Create a children’s book that would depict the beauty and culture of Sub-Saharan Africa for the world! Change leveraged her Zambian roots and the new connections she gained during her 2011 Fulbright Study/Research Award to Zambia for the project, and even learned something about herself in the process.

Born in Zambia and raised in Seattle, Washington, Change has always celebrated the languages and culture of her family. Currently a Ph.D. candidate in Social Work and Developmental Psychology at the University of Michigan, she spent her Fulbright in Zambia working to improve gender equality in education through community outreach and workshops. While working with students, Change was taken aback by the absence of diverse voices and subjects in children’s literature.

“I spent a lot of time around younger children and time in bookstores. I noticed that many of the books available focus on the Western world and lack local references. My Fulbright experience with the Forum of African Women Educationalists of Zambia (FAWEZA) organization empowered me to work on gaps and limitations that I see in communities that I care about,” Kwesele explained.

Part of that gap includes children’s literature. Z is for Zambia: An Alphabet Book introduces the sights and sounds of Zambia to children of all nationalities. The multilingual book is written in three languages commonly used in Zambia (English, Bemba, and Nyanja), and includes visuals and words relevant to Zambia and Sub-Saharan Africa. Instead of apples, bananas, and cats, kids will learn about Africa-related products and places, such as chitenge, a kind of African fabric, nsima, a Zambian staple food, and Victoria Falls, one of the Seven Natural Wonders of the World.

The book is a uniquely international collaboration with two Zambian colleagues and friends: Bellah Zulu, a 2010 Fulbright Foreign Student, and Zanji Sinkala, an alumna of another U.S. Department of State-sponsored exchange program, the Study of the U.S. Institutes Women’s Leadership Program (SUSI-WL). Connecting through Zambia-based organizations and Instagram, the three international exchange alumni decided to use their love of Zambia to increase understanding of the country, even donating the book to Zambian organizations and schools.

Z is for Zambia “will offer children knowledge on other cultures and help [children] appreciate diversity. It will teach them to respect other traditions and ways of life that are very different from their own,” said Zanji, one of Change’s collaborators, speaking about the group’s hope for the book.

Bellah, who studied photography at the New York Film Academy during his Fulbright, provided photographs of Zambian vistas, animals, and clothing to the project. “I appreciate the fact that the Fulbright experience is all about cultural understanding and exchange. For me, collaborating with someone with Zambian roots yet fully American meant that we had an opportunity to influence and continue projecting a positive image of Zambia from inside,” he said.

What does an American-Zambian Fulbright team add up to? “So much change!” Change responded. The book, the collaboration, and her career post-Fulbright all go back to a question she first contemplated on grant: “Why not me?” In Zambia, the United States, or the world of children’s literature, Change will continue to pursue projects and initiatives that she wants to see in the world.

By Aurora Brachman, Fulbright U.S. Student to Kiribati

During my sophomore year at Pomona College I became aware of Kiribati, a small Pacific Island nation at risk of vanishing forever under rising sea levels. Scientists project that in as few as 30 years the entire country could be under water. Little did I know that Kiribati would play an important role in my life, and ultimately lead me to the Fulbright Program.

During my sophomore year at Pomona College I became aware of Kiribati, a small Pacific Island nation at risk of vanishing forever under rising sea levels. Scientists project that in as few as 30 years the entire country could be under water. Little did I know that Kiribati would play an important role in my life, and ultimately lead me to the Fulbright Program.

At the time, there was little information about how the 110,000 citizens of Kiribati were responding to this frightening prognosis. The media representations available were sensationalistic and objectifying, transforming Kiribati into a symbol of climate change, but failing to acknowledge the reality of the daily lives of the I-Kiribati. Despite never having never made a documentary before, I applied for and received a grant through the Pacific Basin Institute to create a documentary making the I-Kiribati and their stories the focal point.

Navigating Kiribati as an outsider is challenging. It is one of the least-developed countries in the world. Eighty percent of the population lives a subsistence lifestyle and there is severely limited access to electricity or running water. Though life will continue on the island for the next few decades, climate change is already making its mark. Some of my closest friends have had their homes destroyed by King Tides – exceptionally high tides that have become more powerful in recent years and are inundating the island, flooding homes and turning fresh water brackish. One friend lost her baby sister to dehydration from drinking water contaminated with oceanwater.

Yet what struck me most about Kiribati had nothing to do with climate change. Kiribati is vibrant in a way I didn’t know anything could be. I have never encountered a group of people that radiate love the way Kiribati people do. During my time there, I befriended a tight knit group of high school students, and they became my liaisons to their world. I was 19 at the time and so were they, and despite our vastly different life experiences, we related as most 19-year-olds do. We commiserated over our anxieties surrounding our encroaching adulthood, discussed our dreams for our futures, and shared our fears about a world paralyzed to act on climate change.

Yet what struck me most about Kiribati had nothing to do with climate change. Kiribati is vibrant in a way I didn’t know anything could be. I have never encountered a group of people that radiate love the way Kiribati people do. During my time there, I befriended a tight knit group of high school students, and they became my liaisons to their world. I was 19 at the time and so were they, and despite our vastly different life experiences, we related as most 19-year-olds do. We commiserated over our anxieties surrounding our encroaching adulthood, discussed our dreams for our futures, and shared our fears about a world paralyzed to act on climate change.

Yet when I asked my friends what they would miss most about Kiribati when they are forced to leave, and the resounding answer was, “the way we treat each other.”

After returning to Pomona, I dreamt of going back to Kiribati. I applied for and was accepted to the Fulbright Program. As someone interested in an artistic field, I didn’t know if my work would be deemed “scholarly enough” or worthy of a Fulbright – but my worries were unfounded. I strongly believe that no one who is interested in applying for Fulbright should be under the false impression that Fulbright is not for them. Fulbright is an incredible resource, and if you have a passion for something, you should absolutely apply.

In consultation with my Kiribati network, I developed a new project for my Fulbright, tentatively titled Life Between the Tides. An anthology series, Life Between the Tides is intended to be a platform of empowerment and self-representation for Kiribati and to build respect, empathy, and understanding of Kiribati people to ease their transition when they are forced to migrate from their country in the near future.

My post-production work will be supported by funding through a granting institution called “Pacific Islanders in Communications,” an organization funded by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting (CPB). I was extremely fortunate to receive the funding as well as a commitment to digital and potential television distribution through the CPB. Life Between the Tides is projected to be released by the beginning of next year.

My post-production work will be supported by funding through a granting institution called “Pacific Islanders in Communications,” an organization funded by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting (CPB). I was extremely fortunate to receive the funding as well as a commitment to digital and potential television distribution through the CPB. Life Between the Tides is projected to be released by the beginning of next year.

My time in Kiribati was one of the most challenging but rewarding experiences of my life. I treasure the lessons it taught me, and the fortitude and resilience I discovered that I never knew I had. Any challenges I face now pale in comparison to what I overcame on my Fulbright. I feel a kind of self-assuredness and self-confidence in my ability as a filmmaker, and a person, that I never had prior to this experience.

This September I will begin my MFA in Documentary Film and Video at Stanford University. I am both anxious and excited to be expanding upon my skills as a filmmaker, storyteller, and artist. In addition to refining my own abilities as a filmmaker, I want to pioneer a new form of participatory documentary filmmaking that works with disenfranchised communities to help equip them with the skills and tools to tell their own stories.

This September I will begin my MFA in Documentary Film and Video at Stanford University. I am both anxious and excited to be expanding upon my skills as a filmmaker, storyteller, and artist. In addition to refining my own abilities as a filmmaker, I want to pioneer a new form of participatory documentary filmmaking that works with disenfranchised communities to help equip them with the skills and tools to tell their own stories.

Compelling stories do not only lie at the center of the Pacific. Now, more than ever, there is a critical need for fostering greater understanding across communities through nuanced storytelling that honors the lives of its subjects. I hope to always use my position as a documentary filmmaker to uplift the narratives of those who struggle to have their voices heard.

Photo credit: Aurora Brachman and Darren James