Letters of Reference/Recommendation

1. You should ideally ask for references from people who have knowledge of your field and the proposed host country and who can speak intelligently about your ability to carry out the proposed project. Recommenders should also comment specifically on the feasibility of your project with the resources available in the country of application, your linguistic and academic or professional preparation to carry out the proposed project, the project’s merit or validity and how well you know and can adapt to the host country’s cultural environment. They are free to comment on any other factors that may be significant to your successful experience abroad. If you are an applicant in the arts, letter writers should discuss your potential for professional growth.

2. You should not use reference letters from university placement services for your Fulbright application; Fulbright recommendation writers must address the specific issues on the Letter of Recommendation form. These issues are specific to the Fulbright Program’s goals. Reference letters addressing them will benefit an application. Letters from a service will be too general and will not add to an application.

3. You should request that your recommenders submit the letter of reference electronically. You must register each reference in the online application by going to Step 5: References/Report. From there, you can register up to three referees and up to two Foreign Language Evaluators. Once registered, the recommender/evaluator will receive an email with login and instructions on how to complete the form. Be sure to:

a) Let your recommender/evaluator(s) know in advance that you are requesting an electronic reference/report.

b) Provide them with a copy or summary of your Statement of Grant Purpose.

c) Remind them that they must print out the PDF version of the reference/evaluation, sign it, and give it to you in the sealed, stamped, self-addressed envelope, which you should provide to them. Once the recommender/evaluator submits the letter electronically, they can still access it to print it out but cannot edit it.

4. As stated above, it is generally best to ask for references from people who have knowledge of your field of study, project and host country. However, you may find it difficult to obtain all three letters of recommendation from people who can fulfill these guidelines. Including references from professors or other field specialists may not always be possible. Although we recommend trying to obtain as many letters as possible from people who meet our guidelines, you can submit a reference letter from anyone that you wish, including supervisors or employees, so long as their recommendation adds to your application.

The Language Evaluation

1. One of the biggest myths about the Fulbright Program is that applicants must be proficient in the host country’s language to even consider applying to a particular country. Although language proficiency can be a factor in competitiveness, you are not ineligible to apply if you lack foreign language proficiency. In general, you should have the necessary language skills to complete the project. Therefore, the onus is on you to design a feasible project.

2. If English is not the official language of your prospective host country, you must submit the Foreign Language Evaluation form. This is true even if:

a) You have no language skills in the host country’s official language (or languages).

b) Your project does not require you use (speak, read, or write) the host country language.

If you have absolutely no language skills in the host country language, indicate this on the Language Evaluation Form and attach a statement outlining what you will do over the course of the next year to obtain a hospitality or survival level of the host country’s language before you would leave on your grant. You would not, in this case, need to have your language skills evaluated. The Fulbright Program’s main goal is to promote mutual understanding between the United States and the host countries, so learning some of the language before going shows a commitment to cultural exchange and demonstrates your sincere interest in learning about the host culture. If you have some knowledge of the host country’s language, you should have your skill level evaluated even if you do not need the language for the project.

3. Foreign language evaluations should come from an instructor in the language. For widely taught languages (Spanish, French and German, for example) you should find a language teacher for an evaluation. For less commonly taught languages, however, you may have an evaluation done by a native speaker of this language. If possible, we recommend obtaining an evaluation from a native speaker who is also a college professor. If that is not feasible, then any native speaker, except a family member, may complete the form. You may find a native speaker, for example, through the host country’s embassy or consulate, cultural center, or international students or faculty on your campus.

4. If your project requires proficiency in multiple foreign languages, you must submit a separate language evaluation for each of the languages required for your project.

5. If you are applying in the Creative and Performing Arts or in the hard sciences you often do not need to speak the host language for your project. In general, the language expectations for these projects are more relaxed than for academic projects. Because of the program’s goal of promoting mutual understanding, however, we recommend that you learn at least a hospitality level of the host language before the grant begins.

Critical Language Enhancement Award

The Critical Language Enhancement Award, also sponsored by the U.S. Department of State, is a supplement to the Fulbright Program and is available for students who have been awarded a Fulbright U.S. Student grant in a country where a critical need language is spoken. Application for a Critical Language Enhancement Award is made in conjunction with the Fulbright Program application.

The languages available for the Critical Language Enhancement Award are Arabic, Azeri, Bengali, Chinese (Mandarin only), Farsi, Gujarati, Hindi, Korean, Marathi, Pashto, Punjabi, Russian, Tajik, Turkish, Urdu, and Uzbek. Additional languages may be added and will be listed on the website.

The Critical Language Enhancement Award’s purpose is to cultivate language learning prior to and during the Fulbright grant period and beyond. Ultimately, awardees will achieve a high level of proficiency in a targeted language and will go on to careers or further study which will incorporate the use of this and/or related languages.

In 2010-11, up to 150 Critical Language Enhancement Awards will be available for grantees to pursue in-country training for between three and six months.

For further details, please see Critical Language Enhancement Award.

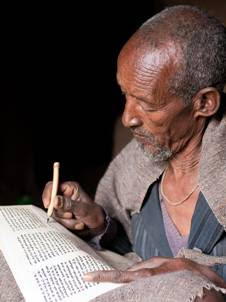

As a scholar of the development of book technology, I have spent a lot of time studying physical objects and wondering about the mindset craftsmen had while producing books in the Ancient and Medieval periods. Since the production of manuscript books in Europe died out centuries ago, it is impossible to ask the producers about their techniques. The tradition of manuscript production that exists (in a reduced state) in the Islamic world is different enough from the one practiced during historical Christendom to limit its utility for the study of traditional European bookmaking. That is why I was excited, during the course of my research, to discover that manuscript bookmaking still survives in the Christian highlands of Ethiopia; it was simply a matter of getting the time and funds to go.

As a scholar of the development of book technology, I have spent a lot of time studying physical objects and wondering about the mindset craftsmen had while producing books in the Ancient and Medieval periods. Since the production of manuscript books in Europe died out centuries ago, it is impossible to ask the producers about their techniques. The tradition of manuscript production that exists (in a reduced state) in the Islamic world is different enough from the one practiced during historical Christendom to limit its utility for the study of traditional European bookmaking. That is why I was excited, during the course of my research, to discover that manuscript bookmaking still survives in the Christian highlands of Ethiopia; it was simply a matter of getting the time and funds to go.