By Anna O. Giarratana, Fulbright U.S. Student to Switzerland

“Food is a universally vital part of our lives, representing history, traditions, and culture. Each of us relies on food not only to survive, but to comfort ourselves, communicate with others, and connect us to our forebears.”

—Sam Chapple-Sokol

When I started my Fulbright at the Zurich Center for Neuroeconomics in Switzerland, I was largely excited about the professional opportunity before me; I had just finished the PhD portion of my joint MD-PhD program, and I was joining a research lab on the forefront of conducting experiments in the nascent field of neuroeconomics. The field, studying how people make decisions, brings neuroscientists like me together with economists, computer scientists, and psychiatrists. In addition to my research, I was also eager to spend my weekends exploring my hobby interest, traditional food—in particular, traditional cured meat products. What I didn’t anticipate when I started my Fulbright was how important those culinary trips would be in giving me a sense of community within the country.

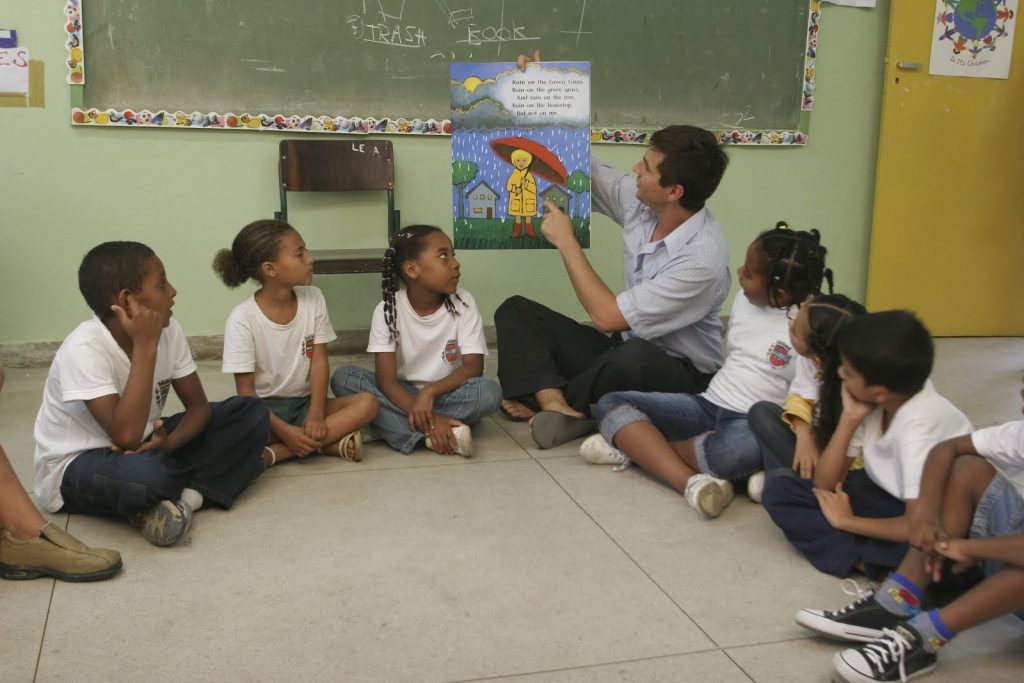

Caption: Enjoying saucisse aux choux in Orbe.

In my first few weeks, I researched online to identify fall festivals highlighting traditional Swiss cured meats. The last weekend in September, armed with Swiss Federal Railways (SBB) Transit and Google Maps, I set off to find the Fête de la Saucisse aux Choux à Orbe. After two hours of rail travel and walking, I found myself in the small hilltop town of Orbe, transported back centuries as I watched local artisans make the famous saucisse aux choux, a local sausage made with cabbage. My efforts to engage the local artisans in discussion about their process suffered an initial set-back when I tried speaking German, which I had studied in preparation for my move to Zurich. I was now in French Switzerland. Uh oh.

What are the French words for “What is this?” again? Luckily, in response to my blank stare, the artisans switched to German and then to Italian, and I was able to muddle through the exchange. I learned that day that the Swiss tend to be fluent in at least two of the national languages, in addition to English, inspiring me to dedicate myself more diligently to my language studies.

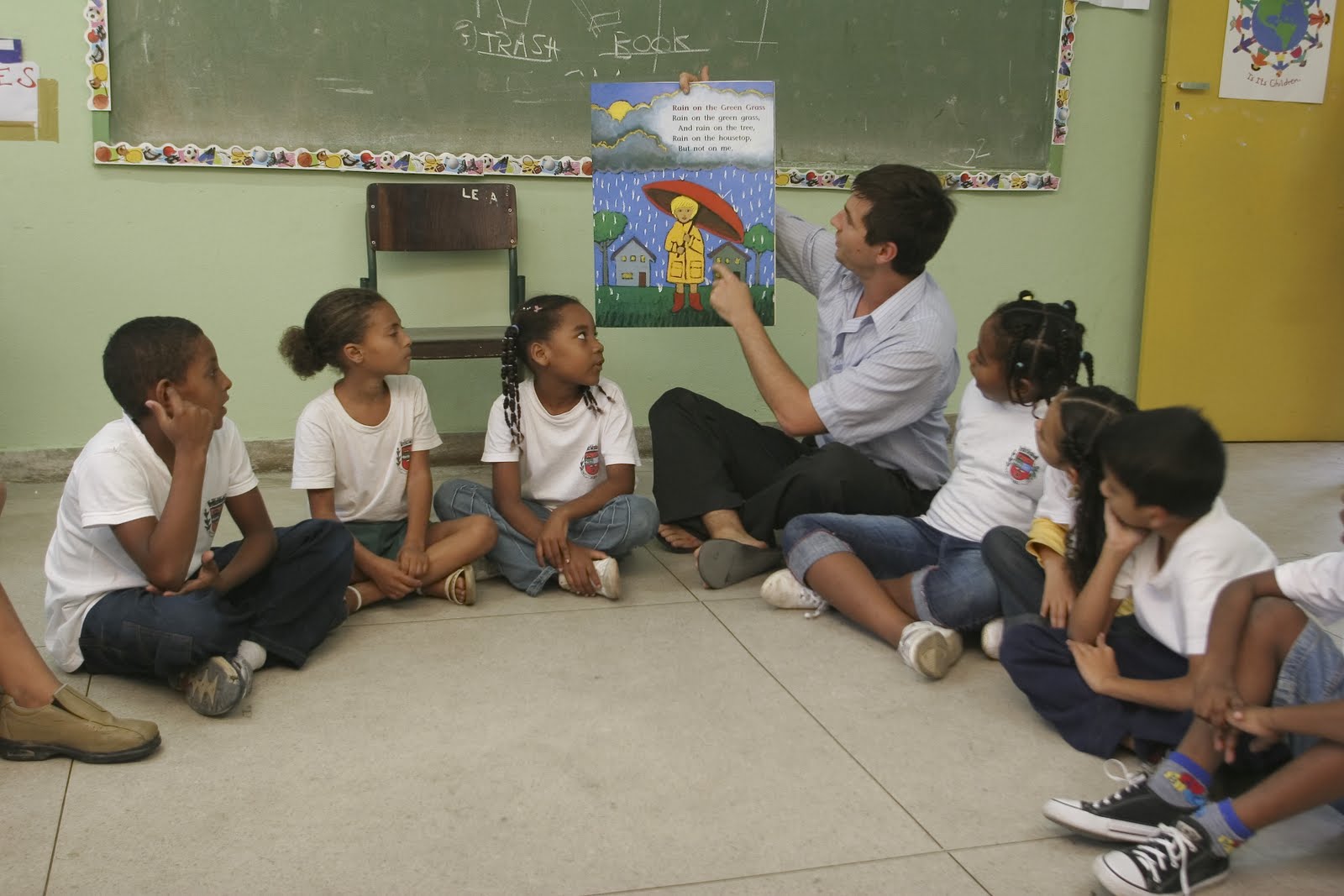

Caption: Learning to make kalbsbratwurst at Olma Messen.

In the following months, I explored Switzerland, a small country but one brimming with unique culinary traditions. I joined a wild food foraging group in Zurich, traveled to St. Gallen for the Olma Messen agricultural trade show; to Porrentruy for the “Feast and Market,” Fête et Marché de la St-Martin; to Chur for the fall exhibit, Guarda Herbstmesse;, to Bonvillars for the Marché aux Truffes; to Gruyères to the La Maison du Gruyère; to Lucerne for Käsefest; and to Ticino for its Stranociada carnival. And, along the way, I gained a greater understanding—through food—of Swiss history. I learned about the different cantons (member states) that make up Switzerland, the languages they speak, the traditions they practice, the products they create, and the values they hold.

Caption: View of Gruyères; Vineyards at the Truffle Market in Bonvillars.

Most importantly, it was through these travels and my bumbling German/French/Italian questions that I made my best friends, both Swiss locals and other internationals like myself, over our shared love for food. We sustained these cross-cultural friendships by creating a rotating dinner group, where we took turns hosting and making our native food or traditional Swiss foods. I learned to make capuns and härdöpfel pizokel from the Graubünden region of Switzerland, enjoyed moqueca from Brazil, and taught others how to make my favorite Italian-American family recipe, potato gnocchi. We shared food, wine, and anecdotes from our time and travels, domestically and internationally. I heard firsthand about the importance of the direct democracy system in Switzerland, which results in voting on quarterly referendums. I learned more about life in India—its different regions, the way the university system works, and how highly valued a government job is. In China, the bestselling books placed in the entry display of bookstores are not works of fiction, but nonfiction books highlighting the value of self-improvement. I shared my experiences with healthcare in the United States: as a medical student, I have a vested interest in improving the U.S. healthcare system. I solicited opinions on what works and what doesn’t work, internationally. Beyond interacting with my local community, I have connected to a global audience by describing my Swiss food explorations on my personal blog and Instagram account “The Gastrochemist.” I have heard from homesick Swiss expats, as well as interested people around the world.

Caption: Homemade Swiss Capuns

In light of the COVID-19 pandemic, this idea of a global community created and sustained through food has become even more vital. Serious conversations with my roommates about past crises they have lived through occurred over shared homemade wiener schnitzel. While I have been practicing social distancing, the internet has allowed me to learn about the comfort foods others are making in countries such as Italy, Singapore, and Australia. Meanwhile, I’m sharing some of my comfort food projects, most recently making homemade pasta with a rabbit sauce called tajarin al ragù di coniglio.

I never could have predicted where I would be six months into my Fulbright: alone in a room with the internet, cooking just for myself, but sharing with the world. If this year has taught me anything, it’s that we’ll get through this together, with a little food and a lot of human spirit.

Anna O. Giarratana is an MD-PhD student at Rutgers University – Robert Wood Johnson Medical School. Originally from Franklin Lakes, NJ, she attended Bryn Mawr College where she majored in Chemistry and cultivated her love for global learning. She is passionate about interdisciplinary, multinational work – believing it to be the best way to tackle difficult problems. As a neuroscientist, she has contributed to the field with multiple publications in peer-reviewed journals and presentations at international conferences. For her Fulbright, she worked at the Zurich Center for Neuroeconomics, an innovative interdisciplinary center dedicated to understanding the cognitive process of decision-making.