Editor’s note: In April 2017, twelve Fulbrighters engaged in a week-long service learning project in Williamson, West Virginia, an Appalachian community with valuable lessons to share about sustainability, perseverance, and revitalization. This is the first in a series of blog posts from the Fulbrighters who visited Williamson. The Fulbrighters were asked to focus on their experiences in Williamson, as well as their engagement with local American community leaders. Visit the Fulbright Amizade 2017 Storify for more details on their journey.

There are many stories to be told about Williamson, West Virginia. About Coal Country. About Appalachia. There are stories of drug abuse and diabetes and poverty. Of unemployment and government regulation and presidential elections. Those stories have been told for decades. Those stories continue to be told today by media outlets around the country. They are stories that can be found throughout the country.

Laura Robinson (right), Fulbright U.S. Student alumna (2014-2015, India), talking with Shane from the Williamson Fire Department. Photo by Marcus Cederström.

There are other stories too. Stories of health and wellness and entrepreneurship. Of resilience and revivals and recreation. Of people working to make their communities just a little bit better. Because throughout the country there are groups of engaged citizens identifying problems and finding solutions. These are stories that must be told as well.

In April 2017, I was part of a small group of Fulbrighters that spent a week in Williamson, a small town founded in 1892. Known locally as the heart of the billion-dollar coalfield, the town sits on the border between Virginia and Kentucky, the Tug Fork River compelling its homes and buildings to climb the hillsides above it. Even when coal was king, the population never reached more than 10,000 people. Today that population is slowly declining—the most recent census counted just over 3,000 people.

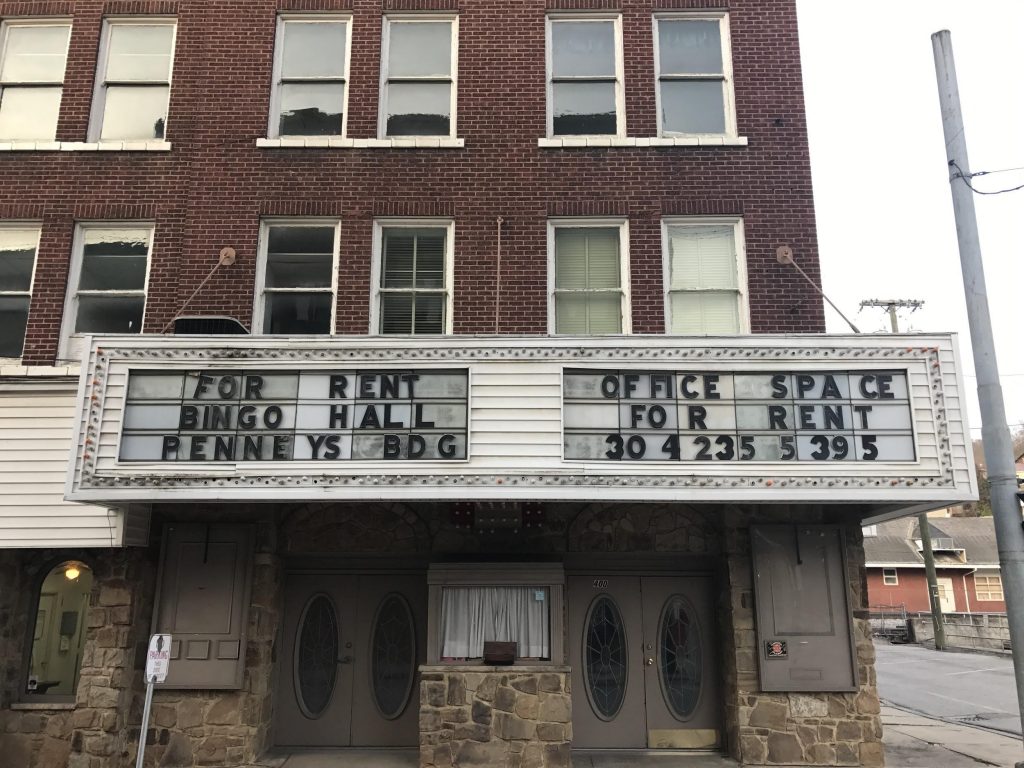

Just off 2nd Avenue in Williamson, WV, this building awaits new tenants. Photo by Marcus Cederström.

The empty storefronts and shuttered windows on 2nd Avenue, Williamson’s main street, are conspicuous, even to an outsider like me. The reasons for Williamson’s population decline are complex and can be attributed to a host of different actors—from government to industry to individuals—and are not unique to Williamson. As a folklorist I’ve learned stories are best told firsthand, in this case by the people of Williamson themselves; because what is less obvious to an outsider is the work that is being done behind the scenes to revitalize those storefronts. For example, the work to combat diabetes in Williamson through the community’s “Healthy in the Hills” initiative, which organizes community walks and works to increase access to healthy foods; or the work to fight the opioid epidemic through a new health and wellness center offering healthcare to people from around the county.

Of course, as outsiders, we still have a responsibility to the community to listen carefully and to help when able. We toured the Williamson Health and Wellness Center as nurses talked with us about their work to ensure that all Mingo County residents have access to quality, affordable healthcare. We met with public defenders who ensure that everyone has access to quality legal counsel. We worked with local carpenters to reclaim lumber from the old American Legion building (not to mention shoveled several tons of gravel), which is set to become a year-round, indoor farmers’ market. We helped prepare raised beds in the community garden, by weeding and even planting onions and lettuce. We visited a local elementary school, hiked to the top of Death Rock with a researcher from the Williamson Health and Wellness Center, attended a community forum at the high school; and all the while, we had the chance to speak to the people who call Williamson home as they showed us their community.

Fulbright U.S. Student Program Alumni Ambassador Ben Cohn (2014-2015, Ghana) and Williamson resident Betty worked together to plant a garden of onions and lettuce in the community garden. Photo by Marcus Cederström.

As Fulbrighters invited into the community, we were asked to help tell Williamson’s story. But the people of Appalachia have had their stories told by others for too long. Instead, what follows are their own words as they honor their community while continuing to shape it. The people featured here gave their time generously. They expressed conflicting political views, economic views, social views. Some were enduringly optimistic while others spoke openly about moving away one day. Even so, this small group of people loves where they live; And every day, they work to make it just a little bit easier for the thousands of other people in Williamson to love where they live.

Williamson’s Own Words from Marcus Cederstrom on Vimeo.

What will become of the many communities that have for years relied on coal? That remains to be seen. But the people of Williamson who met with us share a sense of purpose: make Williamson just a little bit better every single day. This is something, no matter where we live, that we all can strive for.

PERSONAL REFLECTION:

I’m really honored to have been one of the Fulbrighters to travel to Williamson. It was a complicated experience. We were introduced to so many people, so many different ideas and viewpoints, so many conflicts and solutions. I struggled the entire trip to balance the obvious curation of the trip and focus on sustainability with the very serious issues that are forcing more and more people to leave the town. A week is nothing though. Especially for a group of outsiders to come into a community and try to understand it. That’s where my Fulbright time in Sweden came in handy. While I spent about nine months in Stockholm, I conducted fieldwork with people in southern Sweden for just over a week. To ensure that I made the most of my time, I had to learn to quickly make connections with the people I met. To find common ground. To ask questions that were inquisitive, but not invasive. Those are skills I developed while a Fulbright U.S. Student researcher in Sweden and they are skills I am continuing to develop today. Those are also skills that served me well while in Williamson.

The people we met along the way who were so generous with their time, the other Fulbrighters who challenged and engaged each other, the Amizade crew who made so much of this possible, all helped to make this a positive learning experience that encouraged the cultural partnerships that Fulbright strives to cultivate. It’s experiences like these that make the Fulbright Program not just memorable to the people in the program, but vital to the continued focus on mutual understanding between different countries and communities. With a diverse group of people from several different countries, we each brought something unique to the group and to Williamson.

I hope to return to Williamson one day and have kept in touch with many of the people I met there. I have also shared the short film I made with the people I met. Since then, the film has been viewed nearly 1,000 times with several people commenting privately and on social media about how important it was to see the many successful ongoing initiatives in and around Mingo County. That’s what I strive to do as a folklorist. By creating public programming, I can use my platform to amplify other voices. In doing so, I hope that our work there has a long-term effect by making people more aware of the struggles and triumphs of small-town America, while encouraging people to question their assumptions about a place that has long been stereotyped.

I believe that the film, the blog post, and the images we shared along the way, all did that. They amplified the voices in Williamson that are working so hard to help Williamson succeed. Programs like this one, with twelve Fulbrighters, compound that. I can’t even imagine just how many people in countries around the world are now familiar with the work in Williamson, West Virginia. And that, to me, is what the Fulbright Program is all about.

1 Comment

I hope that this organization can continuing their service to others while improving the communities they help. Good work in your achievements at Williamson.