The notebook was palm-sized with a fading yellow leather cover and fell open in my hand as I took it from the box full of other journals filled with the same spidery scrawl. My heart pounded as I flipped through its pages to the crucial month: June 1915, when the explorer Hiram Bingham’s dreams of excavating Inca cities died. And there, in angry handwriting that all but cut through the page, a Peruvian intellectual named Luis E. Valcárcel recorded what he really thought of the Yale Peruvian Expedition, which had exported Machu Picchu’s artifacts to New Haven, Connecticut. I had applied for a Fulbright study/research grant to Peru in the hope that I could find sources that might let me reconstruct Valcárcel’s challenge to the expedition. To find his actual journal – I was moved beyond belief.

The notebook was palm-sized with a fading yellow leather cover and fell open in my hand as I took it from the box full of other journals filled with the same spidery scrawl. My heart pounded as I flipped through its pages to the crucial month: June 1915, when the explorer Hiram Bingham’s dreams of excavating Inca cities died. And there, in angry handwriting that all but cut through the page, a Peruvian intellectual named Luis E. Valcárcel recorded what he really thought of the Yale Peruvian Expedition, which had exported Machu Picchu’s artifacts to New Haven, Connecticut. I had applied for a Fulbright study/research grant to Peru in the hope that I could find sources that might let me reconstruct Valcárcel’s challenge to the expedition. To find his actual journal – I was moved beyond belief.

Four years later, that feeling of good fortune – that rare privilege of cutting through the official version to get at the raw emotions of the past – has not faded. Just two months ago, I was lucky enough to publish a popular history based on my Fulbright research in Peru. Titled Cradle of Gold: The Story of Hiram Bingham, a Real-Life Indiana Jones, and the Search for Machu Picchu, the book explains how Bingham’s search for the last cities of the Incas helped ignite modern Peru’s passion for pre-Columbian history and incited a furious controversy over whether or not artifacts should be exported from their country of origin. The experience has been incredibly positive, but it hardly matches those moments in Peruvian libraries when I was a Fulbrighter, when kind archivists pulled me aside and suggested that I look in that box or this journal for the answers I sought. I wrote the book, in part, as a thank you to my local collaborators, to share their work beyond Peru and explain just why Yale University and Peru were still arguing over the spoils of Bingham’s expeditions.

As I write these words, I’m back in Lima again, this time as a graduate student in the Department of History at the University of Texas at Austin, continuing on my chosen career path as a writer and historian. And though I’ve been fortunate, I also know that I got to Peru on Fulbright for some key reasons – sometimes contradictory – shared by other successful applicants who received study/research grants.

1. Let your project choose you. I apologize if that comes off a little Zen. What I mean is, don’t apply solely because it’s the country you’ve always had pinned up on your bedroom wall or because it would be a cool place to research. Instead, think about what you have to give, the key questions that you feel like only you can ask, and then find the place that most needs those questions answered – the only place where those questions can truly be answered. If you do feel a deep connection to the site, all the better – but what makes your application stand-out – whether you’re a graduating senior. a graduate student or a young professional – is the matching of your sensitive questions to the site, your demonstration that you are the best person to ask them in that time and place. At their best, Fulbright projects are urgent, original, sensitive, and deeply serious about their goals and their modern relevance – be it historical analysis, choreography, or learning about local water management. That said…

2. Temper that passion with responsibility. Do your homework. There are questions that are poorly timed, but there are also questions that are so well-timed that they will put you or your project at risk. Once you have an idea of what you want to do, don’t spend months writing and crafting before talking to your Fulbright Program Adviser (FPA) (if you’re applying At-large and not through an FPA, you should still seek out advice from professors, teachers colleagues, etc.) or experts in the country or finding a host institution. Immediately begin making contacts, bouncing ideas off them, making sure that what you want to do is feasible or desired by the host country and institution, laboratory, conservatory, NGO, etc. – and then write. Your application will bear the marks of that collaboration. It will serve a local purpose. It will show that you have already created the relationships that will carry you through if you get to the country and realize that your specific idea is no longer feasible. Which leads me to …

3. Be open beforehand and adaptable once you’re on the ground. Projects do change. Another country’s Fulbright Commission director once told me that she’s surprised when they don’t. Your questions should provoke new questions, which should then change what you’re trying to learn or contribute. Although your application should demonstrate how well-thought-out and sincere your idea is, it should also show that you are not dogmatic – that you’re not looking to confirm old answers, radical or conservative. Be sensitive. Sit and listen. Keep a journal or blog. Realize that what you’re meant to deliver might not be an academic product, but a creative or social one, and vice versa.

4. Understand – and remember – how this project fits into your larger goals. The application process is only the beginning. You should show not only how you’ve reached this moment, but also where you hope to go with it. Be ambitious and bold with your goals, even if they change. Write the book. Make the movie. Create the website. And once you’re on the ground, keep up those connections and deliver, so that you can then turn around – as I’m doing this month – and hand back your finished project with deep, heartfelt thanks to the Fulbright Program and those that helped you along the way. It’s a great, great feeling.

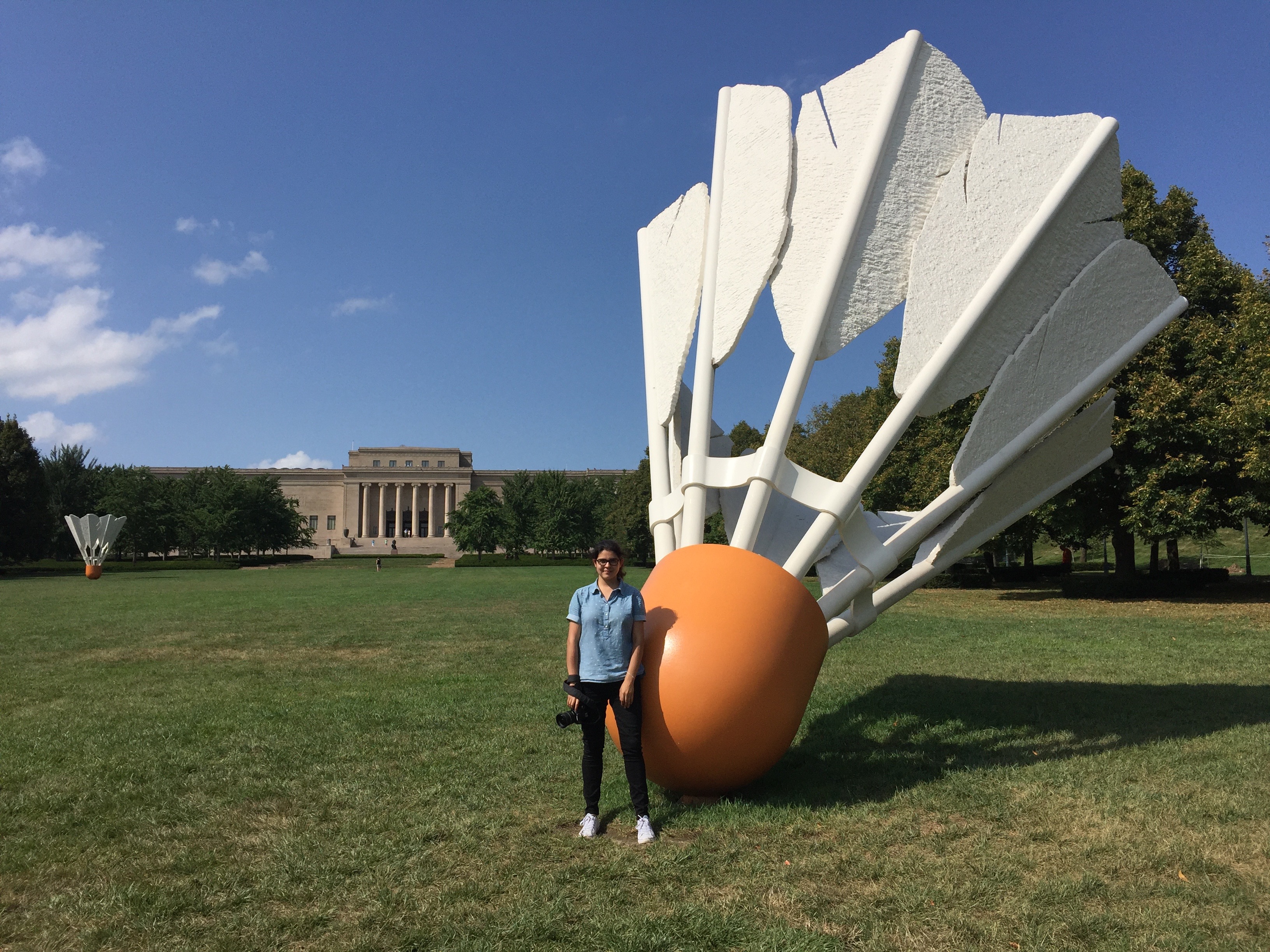

Photo: Christopher Heaney, 2005-2006, Peru, relaxes after climbing Huayna Picchu, the peak overlooking the Inca site of Machu Picchu, whose archaeological history he studied as part of his Fulbright grant.