My Fulbright experience was nothing like what I had anticipated. After the first week, I was ready to return home. I was not off to a good start with my host institution. On the first day at the center, the director greeted me sternly, “How’s your Portuguese?” No, “Hello.” No, “It’s good to meet you.” No, “We’re looking forward to having you here.”

Even after many language classes, I was still not close to where I wanted to be in terms of my comfort level with Portuguese, nor apparently where I needed to be. I was disappointed and frustrated by my inability to communicate effectively. I hired a Portuguese tutor, which I had included in my project proposal. My listening ear improved and I connected better with the language. Yet, language skills affected my research early on and progress moved slowly. Beyond the obvious need for communication, language facility was important for understanding the significance of the issues surrounding my research topic, as well as work being done to address them. It also added value to my overall Fulbright experience.

My ethnographic research examined the structure, operations and effectiveness of non-governmental organizations (NGOs) in Salvador, Brazil, that focused on Afro-Brazilian women and girls. To better comprehend how these entities were meeting the needs of the community, in addition to interviews and participant observation, I attended seminars, conferences, discussion groups and performances. I also taught an English course to adults. The research shifted as I learned that the nonprofits working on issues of gender and race were largely community-based groups and grassroots organizations. Many were loosely structured and without documentation to qualify as an NGO, which limited their ability to apply for significant funding. I asked questions about mission, vision, leadership, resources, outreach, and activities. What was the role of these nonprofits in addressing and combating socio-economic inequities faced by Afro-Brazilian females, a segment of the population often at the bottom of social indicators?

The situation for Afro-descendant women and girls in Brazil is difficult, as racism and discrimination are prevailing factors. The vast majority of Afro-Brazilians live in impoverished conditions without equal access to quality education and healthcare services. Black women in Brazil earn less than half of what Whites earn. In Salvador, the face of domestic labor (namely, maids or nannies) is typically an Afro-Brazilian female, and work is low pay and without labor protection rights. Negative images of Black women in the media are pervasive and violence against women persists. With these challenges, Afro-Brazilian women continue pushing to negotiate their own space within organizations to promote equality.

I came away from my Fulbright experience with a greater awareness and comprehension of the issues confronting Afro-Brazilian females and the organizations supporting their improved conditions. While my expectations were met with my research, I left Salvador wanting to make a positive difference. The earlier challenges I had experienced settling in–finding an affordable apartment, eating out as a vegetarian, excessive heat and no air conditioning, and administrative bureaucracy–faded into memory . I gained more in return – developed greater confidence to travel abroad, learned to live in a new culture and made invaluable friendships.

My advice for applicants:

- Discuss your proposed research topic with professors and colleagues to develop a clear perspective and sense of how you expect to carry out your research.

- Search organizations online to find an affiliate and make contact early.

- Before traveling, clarify any expectations with your host institution.

- Be flexible.

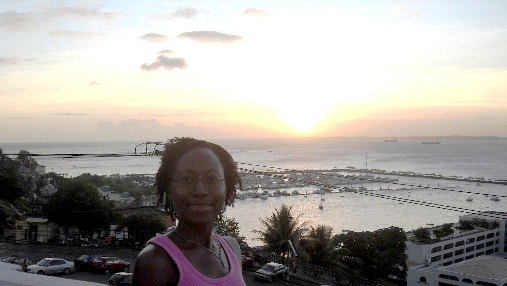

Top photo: Zipporah Slaughter, 2008-2009, Brazil, watching a sunset over the Bay of All Saints (Baía de Todos os Santos) in Salvador; the city of Salvador sits on a peninsula between the Bay of All Saints and the Atlantic Ocean

Middle photo: The all-female Banda Didá performing in the streets of historic Pelourinho; The Didá Education and Cultural Association is a nonprofit in Salvador founded in 1993, by Maestro Neguinho do Samba to improve girls’ confidence and self-esteem through music, percussion and the arts.