Making the Grade: Five Things Every Applicant Should Know About the Fulbright U.S. Student Program Review Process

October 15, 2020By Fulbright Program Staff

Congratulations on submitting your Fulbright application! Now what? Have you ever wondered what happens to your Fulbright application after you hit “submit”? In this post, we’ll shed light on the Fulbright U.S. Student Program’s technical review and National Screening Committee (NSC) processes, illustrating how an applicant becomes a Fulbrighter.

1. First things first… Technical Review

After you hit “submit,” Fulbright Program staff first conducts a technical review of your application materials. Therefore, it pays to thoroughly review country descriptions and eligibility criteria at the beginning of your application journey to ensure that you meet all requirements. Check out our handy application checklist to make sure you don’t forget to include any application materials, too.

During our technical review, we double-check your biographical data, citizenship, transcripts, letters of recommendation, project plans, and more for eligibility and completeness. Make sure that ALL required materials are successfully uploaded and viewable in your online application portal—you won’t be able to add missing documents later! (Hint: Be sure to view and save a PDF copy of your application before submitting—you’ll have both a copy of your application for your records and be able to confirm that all documents are successfully submitted and readable!)

After confirming an application is eligible and complete, it is moved to the National Screening Committee (NSC) for review.

2. The NSC: The Reviewers (and What They Are Looking For)

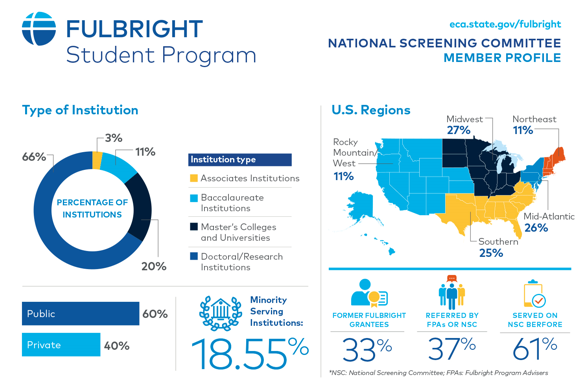

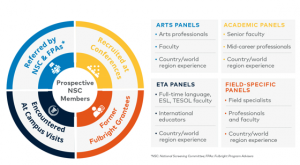

During “NSC Season,” almost 200 committees meet to review and discuss all successfully submitted applications. Each application is sent to a committee of three reviewers a.k.a. NSC members, for a transparent, merit-based review process.

Who exactly are these reviewers? The individuals that review your application are typically university professors with expertise in either a) your academic/professional field, or b) the country or world region where you propose undertaking your Fulbright. Many are Fulbright alumni, while others have been recommended by Fulbright Program Advisers or other NSC members. Reviewers reflect the diversity of the U.S. higher education community and include panelists from minority-serving institutions (MSIs), Historically Black Colleges & Universities (HBCUs), and other underrepresented institutions.

Each committee reviews approximately 60-70 applications in advance of a meeting, scoring each submission based on specific review criteria. While all programs and applicants are unique, NSC reviewers look for well-researched, feasible research and community engagement projects, adequate academic and personal preparation for the proposed country or award, and personal attributes and qualities that illustrate a positive and passionate cultural ambassador of the United States to the world. Be authentically you!

3. NSC Review Day

Throughout November and December, NSC reviewers gather for review meetings. Committees consist of three reviewers and one staff facilitator who directs the flow of the meeting, answers reviewers’ questions about the Fulbright Program, and records results. At these meetings, reviewers discuss each application using a collaborative approach and are welcome to adjust their scores based on their conversation. At the end of the meeting, final scores are tabulated by the staff facilitator, determining which candidates the committee recommends for further consideration during the host country review process.

4. Time & Consideration: The Breakdown

As you may have gathered, the NSC process is a massive undertaking! In 2019, 525 NSC members reviewed approximately 10,400 applications at 175 committee meetings in 6 different cities. From start to finish, more than 11,000 hours are spent screening, reviewing, and scoring each application. And that’s before the in-country review process!

5. The Decision

Based upon the NSC process, applications are designated as “Recommended” or “Non-Recommended.” All applicants are notified of their application’s status, and recommended applicants become “Semi-Finalists!” Recommended applications are forwarded to their respective Fulbright host countries for an additional round of selection, taking into account Fulbright Commission and U.S. Embassy priorities. During this period, Semi-Finalists undertaking research or graduate degree programs may be asked to submit letters of acceptance or affiliation from their proposed institution, so it’s important to receive all necessary documents as soon as possible. In some cases, host countries may also choose to contact Semi-Finalists for short phone or video chat interviews, in order to get a better sense of the person behind the application.

After months of concentrated effort by both applicants and Fulbright Program staff, host countries will share final application notifications on a rolling basis between February and May. Successful applicants are sent an award offer, and are officially known as “Finalists.” Qualified applicants not selected as Finalists may become “Alternates,” or potential awardees that may receive an award offer, should additional funding become available. Non-selected applicants are encouraged to celebrate their Semi-Finalist status, and reapply for the next award cycle. Even those who are not selected should feel extremely proud of their efforts, and know that many parts of the application can be applied to future endeavors beyond Fulbright, such as applying to graduate school.

The Fulbright U.S. Student Program application process is undoubtedly long. We hope this article provides some clarity into the process, and helps you create the best application you can. In writing, editing, and discussing your candidacy with friends, mentors, Fulbright Program Advisers, and other individuals, you may gain greater insight into your passions, your reasons for pursuing a Fulbright, other transferable skills you possess, and insight into our world. Our best wishes for a successful application and bright future!

How to Build a Fulbright Top-Producing Institution: Northwestern University

September 3, 2020

What makes a “Fulbright Top-Producing Institution“? A variety of institutions discuss their efforts to recruit, mentor, and encourage students and scholars to apply for the Fulbright U.S. Student and U.S. Scholar Programs. We hope these conversations pull back the curtain on the advising process, and provide potential applicants and university staff with the tools they need to start their Fulbright journey.

“At Northwestern University, we believe that relationships fuel knowledge. Collaborations among individuals and institutions, globally and locally, drive new discovery and innovation. Fulbright offers a platform to build new relationships and deepen existing partnerships in order to work together to identify new solutions to address the world’s most critical challenges.”

By Northwestern University Staff

Question: Your outstanding faculty/students are one of many factors that led to this achievement. What makes your faculty/students such exceptional candidates for the Fulbright Program?

Our campus is both international- and service-oriented. Northwestern students work, live, and study with students from around the globe. Similarly, our faculty as a whole is deeply international in their background and their outlook. Our students confront and embrace the concept of “difference” daily and are comfortable asking questions that do not have easy answers. We have robust connections with our language faculty who participate on panels and promote the Fulbright Program to their students. Further, a spirit of service pervades this campus. It is rare to find a student who is not actively engaged in socially focused extracurricular activities. Add in the rigorous intellectual climate at Northwestern, and the result is that students are engaged with the world, have empathy for and curiosity about all people, and possess an inquisitive disposition—which, essentially, makes them great Fulbright applicants.

Northwestern’s many strengths are amplified by our culture of collaboration; our research and learning culture is deeply multidisciplinary. In a world where the greatest innovations are produced by teams, not individuals, Northwestern faculty and students are prepared to engage across disciplines and with international partners. This makes them excellent candidates for Fulbright awards because they approach the opportunity already coming from a culture of collaboration across boundaries of all kinds.

What steps have you taken to promote a Fulbright culture on your campus?

We work to keep Fulbright in front of students year-round. We joke that it is “always Fulbright season,” but this is more than a little true. Beginning with the national deadline, we communicate directly with last cycle’s non-recommended applicants and those who began, but did not finish, the application. We see both cohorts as likely candidates for the next cycle. Further, those students who go through our application process are our best advertisement! Our process really gets underway in January with a series of informational meetings which then morph into application workshops in May and June (Northwestern operates on a quarter schedule). In addition to specific Fulbright-focused events, nearly every conversation with students or presentation about fellowships uses Fulbright as an example. During the summer, students work closely with a Fulbright Program Adviser, whom we assign. This close relationship is in addition to their departmental mentors and cements their engagement with our office and the Fulbright application process.

How has your institution benefited from increased engagement with the Fulbright Program?

Northwestern University has been a consistent Fulbright Top Producing Institution for over a decade. Thanks to this record, most students and their faculty mentors see Fulbright as an excellent opportunity to further their interests. We are blessed with a good word-of-mouth network, which encourages students to develop an international outlook early in their education. Fulbright is a well-established aspirational goal for our students, and they see that their chances of receiving an award is within their grasp. They begin on-campus research experiences and language study knowing that developing these skills will help them to extend their local goals onto a global stage.

How does your institution support faculty and administrators who apply to the Fulbright Program?

For administrators who wish to apply to the Fulbright Program, Northwestern’s Office of International Relations promotes the opportunity and provides editorial feedback to staff on their applications.

For faculty, we connect prospective applicants with colleagues who have had Fulbright awards or who have hosted Fulbright representatives on campus and facilitate faculty members’ efforts to bring colleagues with Fulbright grants to campus when possible.

Find out more information about the ways that Northwestern connects with the Fulbright Program here.

What advice do you have for other universities and colleges that want to increase the number of Fulbrighters produced by their institution?

Success with the Fulbright Program starts with an internationally focused institution and strong faculty support. While individuals working with Fulbright applicants might not be able to single-handedly internationalize their campus, they can help faculty see the value in this program and in global opportunities as a whole. Through advertising, individual meetings, group meetings, and conclaves with appropriate faculty, an adviser can facilitate that moment when a faculty member taps a student on the shoulder and says, “You know, you should apply for a Fulbright.”

By Anna O. Giarratana, Fulbright U.S. Student to Switzerland

“Food is a universally vital part of our lives, representing history, traditions, and culture. Each of us relies on food not only to survive, but to comfort ourselves, communicate with others, and connect us to our forebears.”

—Sam Chapple-Sokol

When I started my Fulbright at the Zurich Center for Neuroeconomics in Switzerland, I was largely excited about the professional opportunity before me; I had just finished the PhD portion of my joint MD-PhD program, and I was joining a research lab on the forefront of conducting experiments in the nascent field of neuroeconomics. The field, studying how people make decisions, brings neuroscientists like me together with economists, computer scientists, and psychiatrists. In addition to my research, I was also eager to spend my weekends exploring my hobby interest, traditional food—in particular, traditional cured meat products. What I didn’t anticipate when I started my Fulbright was how important those culinary trips would be in giving me a sense of community within the country.

Caption: Enjoying saucisse aux choux in Orbe.

In my first few weeks, I researched online to identify fall festivals highlighting traditional Swiss cured meats. The last weekend in September, armed with Swiss Federal Railways (SBB) Transit and Google Maps, I set off to find the Fête de la Saucisse aux Choux à Orbe. After two hours of rail travel and walking, I found myself in the small hilltop town of Orbe, transported back centuries as I watched local artisans make the famous saucisse aux choux, a local sausage made with cabbage. My efforts to engage the local artisans in discussion about their process suffered an initial set-back when I tried speaking German, which I had studied in preparation for my move to Zurich. I was now in French Switzerland. Uh oh.

What are the French words for “What is this?” again? Luckily, in response to my blank stare, the artisans switched to German and then to Italian, and I was able to muddle through the exchange. I learned that day that the Swiss tend to be fluent in at least two of the national languages, in addition to English, inspiring me to dedicate myself more diligently to my language studies.

Caption: Learning to make kalbsbratwurst at Olma Messen.

In the following months, I explored Switzerland, a small country but one brimming with unique culinary traditions. I joined a wild food foraging group in Zurich, traveled to St. Gallen for the Olma Messen agricultural trade show; to Porrentruy for the “Feast and Market,” Fête et Marché de la St-Martin; to Chur for the fall exhibit, Guarda Herbstmesse;, to Bonvillars for the Marché aux Truffes; to Gruyères to the La Maison du Gruyère; to Lucerne for Käsefest; and to Ticino for its Stranociada carnival. And, along the way, I gained a greater understanding—through food—of Swiss history. I learned about the different cantons (member states) that make up Switzerland, the languages they speak, the traditions they practice, the products they create, and the values they hold.

Caption: View of Gruyères; Vineyards at the Truffle Market in Bonvillars.

Most importantly, it was through these travels and my bumbling German/French/Italian questions that I made my best friends, both Swiss locals and other internationals like myself, over our shared love for food. We sustained these cross-cultural friendships by creating a rotating dinner group, where we took turns hosting and making our native food or traditional Swiss foods. I learned to make capuns and härdöpfel pizokel from the Graubünden region of Switzerland, enjoyed moqueca from Brazil, and taught others how to make my favorite Italian-American family recipe, potato gnocchi. We shared food, wine, and anecdotes from our time and travels, domestically and internationally. I heard firsthand about the importance of the direct democracy system in Switzerland, which results in voting on quarterly referendums. I learned more about life in India—its different regions, the way the university system works, and how highly valued a government job is. In China, the bestselling books placed in the entry display of bookstores are not works of fiction, but nonfiction books highlighting the value of self-improvement. I shared my experiences with healthcare in the United States: as a medical student, I have a vested interest in improving the U.S. healthcare system. I solicited opinions on what works and what doesn’t work, internationally. Beyond interacting with my local community, I have connected to a global audience by describing my Swiss food explorations on my personal blog and Instagram account “The Gastrochemist.” I have heard from homesick Swiss expats, as well as interested people around the world.

Caption: Homemade Swiss Capuns

In light of the COVID-19 pandemic, this idea of a global community created and sustained through food has become even more vital. Serious conversations with my roommates about past crises they have lived through occurred over shared homemade wiener schnitzel. While I have been practicing social distancing, the internet has allowed me to learn about the comfort foods others are making in countries such as Italy, Singapore, and Australia. Meanwhile, I’m sharing some of my comfort food projects, most recently making homemade pasta with a rabbit sauce called tajarin al ragù di coniglio.

I never could have predicted where I would be six months into my Fulbright: alone in a room with the internet, cooking just for myself, but sharing with the world. If this year has taught me anything, it’s that we’ll get through this together, with a little food and a lot of human spirit.

Anna O. Giarratana is an MD-PhD student at Rutgers University – Robert Wood Johnson Medical School. Originally from Franklin Lakes, NJ, she attended Bryn Mawr College where she majored in Chemistry and cultivated her love for global learning. She is passionate about interdisciplinary, multinational work – believing it to be the best way to tackle difficult problems. As a neuroscientist, she has contributed to the field with multiple publications in peer-reviewed journals and presentations at international conferences. For her Fulbright, she worked at the Zurich Center for Neuroeconomics, an innovative interdisciplinary center dedicated to understanding the cognitive process of decision-making.

By Sarah McLewin, 2018 Fulbright ETA to Morocco

After accepting a Fulbright English Teaching Assistantship to Morocco, I began to imagine exploring all Morocco has to offer—mountains, desert, beaches, and cities, each with a unique history and culture.

But once I arrived in my host city, Rabat, I found myself feeling hesitant to spend my weekends traveling. Instead, during my first few months there, I focused on creating a home in my neighborhood.

Creating My Rabat Home

As I settled in, I learned how to manage my teaching responsibilities and work towards my language goals. But there was also a long list of other things to figure out: Where would I copy materials for class? Or pick up a taxi? Make friends? Get a haircut?

Figuring out all of these things was a trial-and-error process. Eventually, I developed rhythms that were comforting and familiar. I got to know the vendors at the vegetable market by my house so that when I walked through the neighborhood, I felt like a member of the community. I found a perfect café where I could grade papers and practice Arabic with the waitstaff. I became a regular at a hair salon where I had interesting conversations about gender roles in Moroccan society. These daily rituals took me beyond tourist experiences and towards creating a community abroad.

It’s not that I didn’t enjoy touring Morocco; I will always cherish the memories of drinking fresh orange juice while sitting in the cascades of a waterfall in Akchour, or walking through filming locations for Game of Thrones in Essaouira. However, I especially cherish Rabat because it was my Moroccan home.

How to Create Home Abroad

Creating home abroad can show you that new places do not have to feel foreign. The home you create in your new host country lays the foundation for a unique and authentic experience. Wherever Fulbright might take you, here are some practical tips on making it “home.”

- Talk to people – Whether with store clerks, neighbors, or fellow commuters, look for opportunities to create connections with people you pass regularly. The more connections you make, the more you will start to feel a sense that you belong.

- Build local roots – There’s something special about your first few weeks in your city. Delay regional trips so that you set up a strong routine in your new stomping grounds.

- Try familiar things in a new context – Participate in familiar activities far from home. As an avid salsa dancer in the U.S., I was pleasantly surprised to find a vibrant Latin dance community in Rabat. By joining a salsa studio, I made friends from Morocco, Spain, and France, making my Fulbright a truly global experience.

- Try new things – Use your Fulbright as an opportunity to embrace a new hobby, new ways of cooking, and new types of friends. While in Morocco, I found a small gym in my neighborhood that offered Tae Bo for women. I had never tried Tae Bo, but it became a great way for me to meet other women and get to know neighbors.

- Become a regular – Whether it’s a café, restaurant, salon, or market, find a place where you enjoy spending time and can visit regularly. By frequenting the same places, you’re more likely to meet people and establish lasting friendships.

Creating home abroad is a unique process for each person. Whatever it looks like for you, embracing your host country and the home you create will create memories more precious than any tourist excursion can offer.

Exploring the Extraordinary in Your Ordinary

May 29, 2020By Emi Koch, Fulbright-National Geographic Storytelling Fellow to Vietnam, 2019-2020

My dad almost spit out his morning coffee. Puzzled, he cleared his throat.

“Em, are you… sure?”

It was June of last year and I was only thinking to apply for a Fulbright.

“It’s just a thought! I’m just looking into it.”

My words rushed together, the way they do when I get overly excited — which happens a lot. I have ADHD.

He cautiously took a second sip of coffee.

“I mean — isn’t a Fulbright really competitive? Like for people who… you know?“

I knew who he meant. The smart people. Valedictorians. Meredith, who took AP Physics in high school.

Acknowledging his question, I glanced back at my laptop with the Getting Started page on the Fulbright Student Program website staring brightly back at me. The thought that the U.S. State Department would pay me — me! — to travel to a foreign country and devote nine months of my life to collaborating with local residents with a shared curiosity for actionable, positive change seemed beyond my wildest dreams. But the only thing that seemed more impossible than me winning a Fulbright, was me not applying.

I knew my dad’s apprehension was well-informed by my past struggles and letdowns involving my grades, where I had to prove to others that I was capable and yes, even smart…just not in the conventional way.

A few years ago, I was diagnosed with Dyslexia (a learning disability in reading), Dyscalculia (a learning disability in math), and Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) that comes with a mean stutter when public speaking. I was a sophomore in college, and up until that point in my life, I had simply believed that I was slow.

The first time I noticed it, I was five. While I was surrounded by my classmates stretching their hands high up in the air and shouting, “Me! ME!” so that the teacher might call on them first to reveal the coveted, correct answer to the subtraction problem, my hands were clenched tightly around the desk as if we were all about to blast off into the deep, dark unknown forever. I had no idea what was going on… only that so much was going on. Contrary to popular belief, people with ADHD don’t have trouble concentrating. We simply concentrate on everything all at once. The math problem, the other students, the staple shining on the floor and that weird pencil mark on the desk that looks like an acorn are all equally begging for our attention.

In school, this restlessness and attention to peripheral details presented a huge challenge that often resulted in poor grades, dismal SAT scores, and low self-esteem. Surfing was my escape. Sliding down the face of a wave, I knew exactly where I was — physically, mentally, and yes, even spiritually. Unlike the classroom, the ocean was this dynamic force that required my absolute, divided attention — to everything all at once. For the first time, my disabilities were capabilities; misfits that found themselves useful. Mystifying still, the ocean was what ultimately ushered me back into the classroom.

I’m a social-ecologist, meaning I study the relationships people have with our built and natural environment. My focus is on the world’s millions of miles of coastlines and the many isolated, marginalized fishing communities that depend on ever-depleting marine resources. I’ve come to realize that my disabilities are like superpowers — if harnessed properly, they enable me to explore nuances — whether of a physical space, a word in a foreign language, or a feedback loop in a marine social-ecological system. These overlooked subtleties are where the problems hide… those details researchers seek in order to solve problems. In that ability to spot those details lies the ability to find the extraordinary in the ordinary.

Almost one year after being awarded a Fulbright-National Geographic Storytelling Fellowship to Vietnam, I’m still pinching myself that it really happened. My dad spit out his coffee for a second time when I told him the remarkable news.

Before I arrived, people described Vietnam to me as overwhelming. If by that they meant overwhelmingly beautiful, industrialized, and karaoke-curious, I understand. During my time there, I immersed myself in a small-scale fishing community with a rapidly-developing tourism scene and rising sea level just north of Ho Chi Minh City. I lived in the back of a water sports center called MANTA. MANTA trains fishermen to become certified sailing instructors so that they can teach tourists how to sail, and how to use the power of wind energy as an alternative to fossil fuels. MANTA also provides fishermen with an alternative source of income, though this doesn’t mean that the fishermen stop fishing – that’s in their blood.

Since I lived inside a water sports center, I was fortunate to have stand-up paddle boards at my disposal. They were my go-to mode of transportation and earned me credibility among the fishermen for maneuvering my own water craft. I paddled out to sea and met them at their boats for interviews. Sometimes, they invited me on board for breakfast, and we would help ourselves to buckets of freshly-caught soft shell blue crabs, cracking open the not-so-soft shells with our teeth and slurping up the honeyed insides.

In my research, I listened to fishermen’s stories and explored the social and ecological impacts of low fish availability on the human security of ocean-dependent villages along the East Sea. Back on land, my colleagues included several children, ages four to sixteen — the sons and daughters of local fishing families. These kids accompanied me with waterproof cameras to document their lives. Despite the innumerable dissimilarities between my childhood and their own, I can’t help but identify with some aspects. These kids are smart. They are resourceful. I think they’re incredible. But many of them have been told they are not something enough to be successful, or they are too something to have real authority.

I wanted to wash all that social conditioning from their minds and tell them they are powerful. You, kid, are the superhero of your own life story. Our disadvantages, disabilities, discriminations, and disappointments do not define us, because we have the human right to make up our own definitions.