Casey Scieszka, 2007-2008, Mali, with neighborhood friends in Bamako

The first word I learned in the Malian language Bambara was toubab. I must have heard it a hundred times a day, called out to me by children playing with sticks in the street, store-owners having tea on the corner, women pounding millet with babies tied to their backs.

Roughly, it means “whitey.”

There was no way I, the American hodgepodge of northern European ancestors, was ever going to blend in over in West Africa. Not even once I started wearing the local clothes or speaking the language or eating with my hands.

Slowly but surely though, each of the three times I settled into a new neighborhood (in Bamako then Timbuktu then Segou), I heard the word less and less. As I learned all of my neighbors’ names, they started learning mine. Exchanging greetings and names turned into exchanging bits of news, which turned into hanging out under mango trees during 120 degree afternoons, which eventually turned into friendship.

That is where the Fulbright Program does its best work.

Beyond this interpersonal connection, I enjoyed my formal research. I looked at the role of Islam in the education system, which meant that I spent my days doing observations in different kinds of classrooms, interviewing teachers and principals, having conversations with parents and students. I learned a lot about the politics of language, about the perceived differences in moral versus academic education, about finger-pointing and about the effects of decentralization. But all of that academic research would have been missing its real pulse if the Fulbright Program hadn’t allowed for the time and freedom to become a part of the community as well. Issues that I came across in my research became crystallized in the more personal experiences of my new friends and neighbors. Sure, I knew that most Malian girls don’t make it past 6th grade; but that figure meant so much more to me once my neighbors started talking about whether or not it was worth the money to send their twelve-year-old daughter Saran to school anymore.

It’s hard to remember what I even thought of Mali before I lived there. I knew it was hot, had produced some amazing musicians like Ali Farka Touré, and was home to the ever mysterious Timbuktu. Now though, for me, Mali is made up of familiar faces; faces with names, homes, families, favorite foods, favorite songs, jokes, grievances, desires. Mali is now the people that I met.

Hopefully, the vision of America now has one more face to the Malians I met—mine. Americans are too often generalized as loud and uncaring, greedy, rich, and unskilled in foreign language. I did my best to be my best: to listen, to learn, to give in the ways that I could.

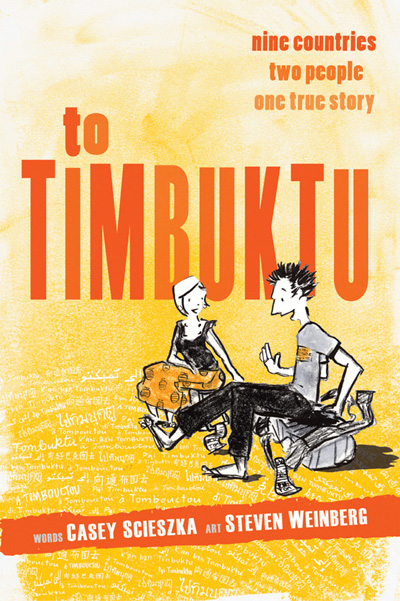

The formal results of my experience were my Fulbright report (which helped members of USAID decide to fund specific foreign language programs in private religious schools they were previously very wary of), the nonprofit I went on to co-found (Local Language Literacy, which is dedicated to creating, printing and distributing books in local languages like Bambara to students free of charge), and the illustrated book To Timbuktu about my two years living in Asia and West Africa that came out at the beginning of this March.

To Timbuktu was a fantastic way to take my Fulbright experience and get it into the hands of a wider audience, to put Mali on the map for more Americans, and to stay in touch with the places and people that had become so dear to me.

My boyfriend and I just went back to Mali this past January—exactly three years since we left at the end of my Fulbright. And sure, when we got out of the taxi, we were bombarded by cries of “Eh Toubab!” But the closer we got to our old home, the more we started hearing calls of “Fatimata! Salif!” And those aren’t other words for “whitey.” They’re our Malian names.

For more information about the nonprofit Local Language Literacy, please visit locallanguageliteracy.org.

For more information about Casey’s book, please visit allthewaytotimbuktu.com.

- Keep repeating to yourself: “Feasibility! Feasibility!” Don’t set yourself up to do some kind of country-wide survey all alone. Be realistic about what one person can look into, how long it will take you, and what you yourself are especially qualified to do/will enjoy doing.

- Look into as many potential affiliates as possible. It’s often really hard to track people down from abroad. Some of these people you contact may not wind up being your official affiliate but could be wonderful people to meet up with once you’re in the country, nonetheless.

- Leave some room for your research to change. That’s one of the best parts of doing a project like this: you have a plan; you do some work and meet some people, learn something new, and wind up going in a direction you might not have anticipated.

- Contact every friend-of-a-friend in that country you possibly can. They might be able to tell you things your r esearch from home can’t, they might have friends who can be your affiliates, and they might even offer to host you when you first arrive! Having a tiny bit in common can go a surprisingly long way when you’re far from home.

1 Comment

This is one of the best blog posts I’ve read in quite some time! Nice work.

Paige

Fulbright Alumni Ambassador, ETA to Thailand 2008-09