Top 5 Fulbright Student Blog Posts of 2020

December 10, 2020Connecting Indigenous Communities: Native American Heritage Month Q&A

November 18, 2020This Native American Heritage Month, we’re highlighting the contributions of outstanding Fulbrighters who live the Fulbright mission through the ways in which they express their identities and their goals. In this Q&A, Fulbright Student Alumni Ambassador Vince Redhouse shares his experiences in Australia, where he learned about the relationship between Indigenous communities and the law.

Vince Redhouse, 2015 Fulbright U.S. Student in Philosophy to Australia

Vince Redhouse, 2015 Fulbright U.S. Student in Philosophy to Australia

Vince Redhouse, the 2015 Anne Wexler Fulbright Scholarship in Public Policy recipient, studied at the Australian National University (ANU) in Canberra, where he completed an MPhil in Philosophy under the supervision of Robert E. Goodin. Vince’s thesis focused on the topic of political reconciliation between settler states and their indigenous citizens. In addition to his master’s program, Vince tutored for a course on Indigenous Culture through ANU’s Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research, was a Visiting Research Fellow at the University of Canberra’s Centre for Deliberative Democracy and Global Governance, gave a TEDx presentation, and through support from both the ANU and the Lois Roth Endowment, visited Utopia, an indigenous community in the Northern Territory, where he was able to learn firsthand some of the issues Indigenous Australians face.

1. Tell us a little about your path to Fulbright. Who or what inspired you to apply?

Vince: My path was different than most. I am a first-generation college student and prior to my junior year of college, I had never heard of Fulbright! I was fortunate that one of my advisers recommended the program to me. There were two things that inspired me to apply: 1. An interest in the relationship between foreign Indigenous people and their settler colonial government; and 2. The opportunity to see if academia was right for me.

2. Tell us a little about your Fulbright research topic and project. What did a typical day as a Fulbrighter look like for you?

Vince: My Fulbright was for a two-year research degree: a Master of Philosophy (MPhil) in Philosophy at the Australian National University. My initial proposal was to examine and apply contemporary deliberative practices to see whether they could be used to dispel the false beliefs that societies hold about Indigenous peoples. What my proposal ended up being, however, was a normative evaluation of how political reconciliation could occur between Indigenous peoples and their settler colonial states. Ultimately, I argued that for political reconciliation to end legitimating settler colonial states, Indigenous citizens must be able to exit the process and reclaim their lands, should reconciliation fail or prove undesirable.

My research process was fairly routine: I commuted to my office(s) and did research at my computer most of the day. My university has an incredible tradition of taking tea twice a day, and I took advantage of that. It was a great opportunity for me to get feedback from professors and other students of all philosophical backgrounds in a friendly and casual environment. I also gave several research presentations, including a talk at the U.S. Embassy in Canberra and a TEDx talk, and was a pro bono tutor (i.e. graduate assistant) for an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander history and culture course taught by ANU’s Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research. I was also a visiting research fellow at the University of Canberra Centre for Deliberative Democracy and Global Governance. From time to time, I was also able to meet and discuss issues with indigenous leaders and activists throughout the country—even spending a couple weeks in a remote indigenous reserve—as well as with members of the Prime Minister and Cabinet’s Indigenous Affairs team.

Caption: Vince at TEDxFulbrightCanberra, and with former U.S. Ambassador to Australia John Berry.

3. How did your identity play a role in your Fulbright experience?

Vince: My identity as a Navajo was absolutely crucial to my Fulbright experience. A lot of the experiences I described above were available to me solely because I was an Indigenous person from the United States. The Indigenous peoples of Australia were just as eager to learn from me as I was from them! For example, I was invited to tutor a course in Aboriginal history and culture in order to share my experiences as an Indigenous person from the United States. Similarly, I was invited to spend time on a remote Aboriginal reserve, where I saw firsthand the impact of Australia’s Indigenous education policies. I was able to share my own experiences about U.S. educational approaches on Indian reservations.

Caption: Vince having dinner and hanging out with his philosophy friends.

4. What is your biggest takeaway from your Fulbright?

Vince: That indigenous communities across the world should be working together. We share so many historical similarities and are working to fight so many of the same battles every day. I truly believe that if we work together and learn from each other that we can do more than just persevere, we can thrive!

Caption: Vince (center back) sharing a meal with co-workers from the University of Canberra’s Centre for Deliberative Democracy and Global Governance.

5. What impact did your research or studies make in your career and local communities?

Vince: My Fulbright experience has had a tremendous impact on my life. It spurred me to go to law school and focus on Federal Indian law, but it also encouraged me to redouble my volunteer efforts working with Native American youth in the southwest United States. Currently, I run a professional alumni mentoring and scholarship program for Native students at the University of Arizona. Since taking over the program, I’ve been able to recruit a larger alumni community to mentor Native students and raise more scholarship funds for our students. My volunteer work collaborates with administrators to create mutually beneficial policy, and my experiences in Australia gave me the confidence to navigate and advocate in that arena.

6. How can native/indigenous students be supported and included in international education?

Vince: Fulbright should be more persistent about reaching out to Tribes, Tribal colleges, and international Indigenous communities about Fulbright opportunities. These connections are important not just for promoting Fulbright, but also for helping Indigenous students once they are abroad. Although Fulbright played a role in helping me make connections with Indigenous peoples in Australia, those connections were always indirect (e.g., a Fulbright alumnus introducing me to someone). Given Fulbright’s expansive alumni network and name recognition, I would like to see it strive to make those connections more directly.

Making the Grade: Five Things Every Applicant Should Know About the Fulbright U.S. Student Program Review Process

October 15, 2020By Fulbright Program Staff

Congratulations on submitting your Fulbright application! Now what? Have you ever wondered what happens to your Fulbright application after you hit “submit”? In this post, we’ll shed light on the Fulbright U.S. Student Program’s technical review and National Screening Committee (NSC) processes, illustrating how an applicant becomes a Fulbrighter.

1. First things first… Technical Review

After you hit “submit,” Fulbright Program staff first conducts a technical review of your application materials. Therefore, it pays to thoroughly review country descriptions and eligibility criteria at the beginning of your application journey to ensure that you meet all requirements. Check out our handy application checklist to make sure you don’t forget to include any application materials, too.

During our technical review, we double-check your biographical data, citizenship, transcripts, letters of recommendation, project plans, and more for eligibility and completeness. Make sure that ALL required materials are successfully uploaded and viewable in your online application portal—you won’t be able to add missing documents later! (Hint: Be sure to view and save a PDF copy of your application before submitting—you’ll have both a copy of your application for your records and be able to confirm that all documents are successfully submitted and readable!)

After confirming an application is eligible and complete, it is moved to the National Screening Committee (NSC) for review.

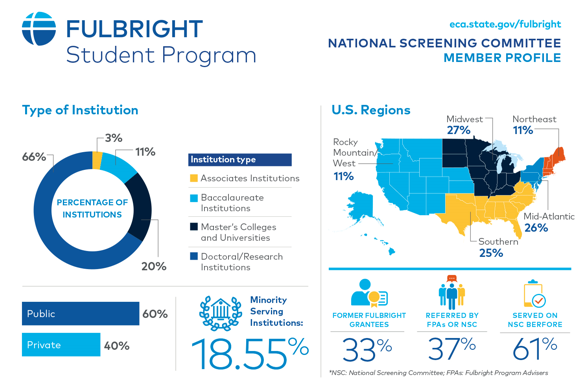

2. The NSC: The Reviewers (and What They Are Looking For)

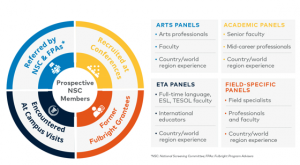

During “NSC Season,” almost 200 committees meet to review and discuss all successfully submitted applications. Each application is sent to a committee of three reviewers a.k.a. NSC members, for a transparent, merit-based review process.

Who exactly are these reviewers? The individuals that review your application are typically university professors with expertise in either a) your academic/professional field, or b) the country or world region where you propose undertaking your Fulbright. Many are Fulbright alumni, while others have been recommended by Fulbright Program Advisers or other NSC members. Reviewers reflect the diversity of the U.S. higher education community and include panelists from minority-serving institutions (MSIs), Historically Black Colleges & Universities (HBCUs), and other underrepresented institutions.

Each committee reviews approximately 60-70 applications in advance of a meeting, scoring each submission based on specific review criteria. While all programs and applicants are unique, NSC reviewers look for well-researched, feasible research and community engagement projects, adequate academic and personal preparation for the proposed country or award, and personal attributes and qualities that illustrate a positive and passionate cultural ambassador of the United States to the world. Be authentically you!

3. NSC Review Day

Throughout November and December, NSC reviewers gather for review meetings. Committees consist of three reviewers and one staff facilitator who directs the flow of the meeting, answers reviewers’ questions about the Fulbright Program, and records results. At these meetings, reviewers discuss each application using a collaborative approach and are welcome to adjust their scores based on their conversation. At the end of the meeting, final scores are tabulated by the staff facilitator, determining which candidates the committee recommends for further consideration during the host country review process.

4. Time & Consideration: The Breakdown

As you may have gathered, the NSC process is a massive undertaking! In 2019, 525 NSC members reviewed approximately 10,400 applications at 175 committee meetings in 6 different cities. From start to finish, more than 11,000 hours are spent screening, reviewing, and scoring each application. And that’s before the in-country review process!

5. The Decision

Based upon the NSC process, applications are designated as “Recommended” or “Non-Recommended.” All applicants are notified of their application’s status, and recommended applicants become “Semi-Finalists!” Recommended applications are forwarded to their respective Fulbright host countries for an additional round of selection, taking into account Fulbright Commission and U.S. Embassy priorities. During this period, Semi-Finalists undertaking research or graduate degree programs may be asked to submit letters of acceptance or affiliation from their proposed institution, so it’s important to receive all necessary documents as soon as possible. In some cases, host countries may also choose to contact Semi-Finalists for short phone or video chat interviews, in order to get a better sense of the person behind the application.

After months of concentrated effort by both applicants and Fulbright Program staff, host countries will share final application notifications on a rolling basis between February and May. Successful applicants are sent an award offer, and are officially known as “Finalists.” Qualified applicants not selected as Finalists may become “Alternates,” or potential awardees that may receive an award offer, should additional funding become available. Non-selected applicants are encouraged to celebrate their Semi-Finalist status, and reapply for the next award cycle. Even those who are not selected should feel extremely proud of their efforts, and know that many parts of the application can be applied to future endeavors beyond Fulbright, such as applying to graduate school.

The Fulbright U.S. Student Program application process is undoubtedly long. We hope this article provides some clarity into the process, and helps you create the best application you can. In writing, editing, and discussing your candidacy with friends, mentors, Fulbright Program Advisers, and other individuals, you may gain greater insight into your passions, your reasons for pursuing a Fulbright, other transferable skills you possess, and insight into our world. Our best wishes for a successful application and bright future!

This National Hispanic Heritage Month, we’re highlighting the contributions of outstanding Fulbrighters who live the Fulbright mission through their identities and goals. In this Q&A, Fulbright Student Alumni Ambassadors Tania Aparicio, Maren Lujan, and Abraham De La Rosa share their experiences and discuss inclusion and equity in international education, especially as it relates to their own experiences and identities.

Tania Aparicio, 2018 Fulbright U.S. Student in Sociology and Film to Mexico

In Mexico, Tania conducted qualitative research for her doctoral dissertation, which focuses on the decision-making process involved in film curatorship. Her doctoral thesis proposes that curatorship is a collective process influenced by the principles that organizations stand for and not based on individual taste, as other scholars have previously claimed. Working with the curatorial team at the Cineteca Nacional de Mexico, Tania conducted participant observation on how film curators make and justify programmatic decisions.

Abraham M. De La Rosa, 2018 Fulbright U.S. Student in Public Administration to Italy

Abraham earned a master’s degree in Public Administration through the SDA Bocconi School of Management in Milan, Italy, where he studied how the public and private sectors can collaborate to tackle new challenges across the globe. As part of this program, he interned with Officine Innovazione-Deloitte Italy and Rise Products to conduct market research on the global flour industry and upcycling products. In addition to his coursework, Abraham worked on a capstone research project focused on social impact bonds for refugees in the European Union, which he presented at the European Investment Bank in Luxemburg.

Maren A. Lujan, 2017 Fulbright U.S. Student in Anthropology to Sierra Leone

Maren’s Fulbright research focused on studying social and cultural structures impacting women’s access to healthcare. While in Sierra Leone, Maren conducted ethnographic research in a rural town, as well as system analysis at the regional and national levels. She worked with a Sierra Leonean research assistant and collaborated with a non-governmental organization, FOCUS 1000, to employ participatory research techniques at the local level.

1. Tell us a little about your path to Fulbright. Who or what inspired you to apply?

Tania: Fulbright is one of the most prestigious grants for graduate students. I had looked into programs to fund research in Mexico, and found my doctoral dissertation project, which is arts-based, was a good fit for the Fulbright Open Study/Research Award to Mexico. When I started my application in early May, I attended an informational session at my university. There, I met Katie Wolff, Assistant Director of Global Engagement & International Programs, and The New School’s Fulbright Program Adviser. She met with me and helped me set up a timeline to get my application materials completed during the summer. I could not have done it without her.

Abraham: I had known about Fulbright for a couple of years, but I had the misconception that Fulbright was for STEM students to continue undergraduate research projects. It was not until a few years ago that I discovered that there are a lot of different Fulbright awards available across the world. While I was working full time, I discovered that you could pursue a master’s program through Fulbright. I found an award that aligned with my educational and professional background, as well as what I wanted to continue to learn, and I decided to apply. The process was quite hectic, especially since I was working. Luckily, I had the support of my supervisor and roommate, who made sure I stayed with my application and submitted.

Maren: I don’t recall exactly what prompted me to apply. I wasn’t even entirely sure what Fulbright was before applying. A friend of mine had completed a program through Fulbright, so I was familiar with the name; perhaps a professor mentioned it offhand as an option. I applied, got it, and then figured it out from there!

2. Tell us a little about your Fulbright research topic and project. What did a typical day as a Fulbrighter look like for you?

Tania: I spent nine months in Mexico City gathering qualitative data for my doctoral dissertation, which investigates film curatorship in two important arts organizations. I wanted to understand how curatorial decisions are made, because they impact the film culture that millions of people have access to. My first case was the Museum of Modern Art in New York City and the second was Cineteca Nacional (The National Film Center) in Mexico City.

Caption: Tania Aparicio on her Fulbright, posing in front of her host institution, Cineteca Nacional in Mexico City, Mexico.

As a Fulbrighter, I conducted participant observation as a member of the Programming Department with Cineteca Nacional. I spent most of my time with the head curators, who decide what films 1.3 million annual visitors will watch in the film center. I was lucky to attend private film screenings and observed their firsthand reactions to the films they were judging, how they classified them, and the type of evaluation processes they engaged in. I also shadowed each member of the department, including theater managers, shipping employees, film rights managers, assistants, and interns. During the last three months of my stay, I conducted in-depth interviews with film curators who worked for other organizations, as well as other important industry members, in order to get a fuller idea of the field and of how Cineteca Nacional fit in the larger cultural landscape in Mexico. I also conducted workshops for local graduate students on how to conduct qualitative research when studying forms of cultural production, such as cinema.

Abraham: My Fulbright allowed me to pursue a Master of Public Administration degree (MPA) through the SDA Bocconi School of Management in Milan, Italy. I primarily attended classes as a graduate student and my typical day really varied. My first semester focused on courses and content, while during the second semester, I worked with classmates on a research project focused on public-private partnerships and social impact bonds for refugees in Europe. After completing the research project towards the end of the semester, I completed coursework while interning with a consulting company.

In addition, I volunteered in the local community and went hiking out of the city during the weekend. It’s hard to describe a typical day, since it really changed depending on the month and where I stood in my program.

Maren: My research topic looked at women’s health in rural Sierra Leone from a social and cultural perspective. A typical day for me was walking around the rural town where I was staying, or visiting one of the many surrounding villages, and talking with individuals about their health and their experiences with the health system.

Abraham De La Rosa at the United Nations Office at Geneva during a multi-day excursion in Switzerland, as part of his master’s degree program.

3. How did your identity play a role in your Fulbright experience?

Tania: I often had conversations about how, as an immigrant from Peru, I am from “here and there,” to borrow a phrase from Alexandra Delano, the Co-Chair and Associate Professor of Global Studies at The New School, who has written about diaspora policies, integration, and social rights beyond borders. In my experience, I received pushback from people who wanted to label me exclusively as Peruvian, rather than Peruvian-American. Nevertheless, I do not think of myself only as Peruvian anymore, and I haven’t for a long time, even though I moved to the United States as an adult and without my family. I am grateful for the opportunity I had to reflect and discuss my identity as an immigrant with my peers in Mexico. I came to realize how formative my immigration trajectory has been, and how I could never be who I’ve become anywhere else but in the United States.

Abraham: My identity played a big role in my Fulbright experience, since my courses were discussion-based. One of the topics we kept going back to was how governments and the private sector can better serve their communities. During these discussions, I was able to share with my classmates my Mexican and American experience in the United States. For most of them, it was their first time interacting with an immigrant and first-generation college student. Being able to have these deep conversations with my classmates and members of the community allowed me to share a side of the United States not normally shown in mainstream media.

Maren: Being light-skinned in Sierra Leone and West Africa categorizes you as “apotho” (white/foreigner), and with that comes privilege and certain expectations, especially in rural areas. Residents’ experiences with foreigners is commonly through foreign aid: when I approached people to talk about their health, I was assumed to be a doctor, and very often get asked for medical advice and medicine. This was also part of my research on the health system: considering the impact of international aid. A few distrusted my intentions, so a lot of my work was also building trust.

Additionally, being American, there were often assumptions of wealth—I did want individuals to understand that there is also poverty, racism, and inequality in the United States. As a first-generation Mexican-American, it felt important to me to share my experiences, but navigating those conversations could be difficult given the disparities and differences in access, and given that poverty in the United States looks very different from poverty in rural Sierra Leone.

Abraham De La Rosa participating at the Seeds&Chips Summit through his internship in Milan, Italy.

4. What is your biggest takeaway from your Fulbright?

Tania: Where, what, and how a new place becomes home is always unexpected. Also, every Fulbrighter I’ve met since my grant started are members of this amazing community of kind and insightful human beings.

Caption: Tania Aparicio visiting Palenque archeological site in Mexico.

Abraham: One of the biggest takeaways from my Fulbright is realizing that we have a lot in common with others around the world. My master’s program was composed of people from 16 different countries, and I was surprised constantly by how our countries worked similarly to try to help our communities. I found myself sometimes realizing that what I understood about a country or situation from a U.S-based perspective was not the full story. Through trying to learn mutually from others, I was able to also see a different reality about their countries and societies. These are skills that I found extremely helpful, and that I continue to use even upon my return to the United States.

Maren: Being a first-generation college graduate, I’m still amazed that programs like Fulbright exist. The fact that I was given the opportunity and funding to pursue my own research is still unbelievable to me. This has set me up for a PhD. While I will need to continue to pursue funding for my research, I do feel a sense of confidence now in seeing that my work has value, and that someone was willing to fund it.

5. What impact did your research or studies make in your career and local communities?

Tania: I could not have completed my dissertation research without Fulbright. Due to this research, I have presented in conferences in both Mexico and the United States, prepared articles for publication in peer-reviewed journals, and I’m currently writing my PhD dissertation. My work is a comparative study of film curatorship in a U.S.-based non-profit and a Mexico-based public organization—this comparative approach is yielding new knowledge for cultural managers and practitioners.

Abraham: My Fulbright allowed me to continue to advance professionally. Since my return to the United States, I have been working with a non-profit organization, The Forum on Education Abroad, applying a lot of my acquired knowledge. The organization works directly with universities and study abroad providers to ensure best practices in the field of education abroad.

Maren: My research focused on the use of participatory practices: how to engage with community while conducting research, and considering the impact of that research on them. I currently facilitate a community health plan with a variety of health service providers and engage with stakeholders to maximize impact. I’ve been able to re-focus the work to community impact and implement strategies for engaging with residents, folding health equity into the action plan.

Abraham De La Rosa with two classmates at La Scala Opera House in Milan, Italy.

6. What does equity and inclusion look like in international education/study abroad?

Tania: It looks like networks of people helping each other move up and forward together. For example, it looks like first-generation college students learning about programs like Fulbright and getting the mentorship and support to navigate the application process.

Tania Aparicio touring Mexico City with fellow Fulbrighter.

Abraham: This is a very complex question and I think many in the field of international education are trying to answer this. Equity, diversity, and inclusion are guiding principles that should be embedded in every aspect of international education, and considered prior to a program even beginning. When a program or an opportunity abroad is being designed, underserved and unrepresented populations should be kept in mind throughout the entire design process. This includes, but is not limited to, the mission and goals of the program; the populations for whom the program is intended; the application process; financial assistance; and the support that will be provided to each participant before, during, and after their experience abroad. If underserved and unrepresented participants are not kept in mind from the very beginning, trying to ensure equity and inclusion at the end of the process will be much more difficult and perhaps ineffective.

In a broader sense, we hope that everyone can participate in international education, and that each participating cohort is representative of the vast diversity of the United States. The goal is an opportunity where everyone feels welcomed and equally served, regardless of gender, race, identity, or background, and where you can feel safe sharing who you are and learn from others. I think the field of international education continues to improve and grow, but we can all continue to learn and share with one another to continue to grow.

Maren: I think when discussing equity and inclusion for study abroad, we want to look at the students who have historically been disenfranchised or wouldn’t have access otherwise. Recently, someone mentioned that study abroad demographics mirrored higher education numbers. If you consider all the barriers to education for low-income, minority, disabled students, and others, we have to ask: are we maximizing equity, or maintaining a status quo where only the elites and outliers have access to study abroad and international education? I got lucky learning about Fulbright and was given the opportunity of a lifetime, but I know in that respect, I’m still an outlier.

Abraham De La Rosa hiking in Lecco, Italy, located 30 km outside of Milan.

How to Build a Fulbright Top-Producing Institution: Northwestern University

September 3, 2020

What makes a “Fulbright Top-Producing Institution“? A variety of institutions discuss their efforts to recruit, mentor, and encourage students and scholars to apply for the Fulbright U.S. Student and U.S. Scholar Programs. We hope these conversations pull back the curtain on the advising process, and provide potential applicants and university staff with the tools they need to start their Fulbright journey.

“At Northwestern University, we believe that relationships fuel knowledge. Collaborations among individuals and institutions, globally and locally, drive new discovery and innovation. Fulbright offers a platform to build new relationships and deepen existing partnerships in order to work together to identify new solutions to address the world’s most critical challenges.”

By Northwestern University Staff

Question: Your outstanding faculty/students are one of many factors that led to this achievement. What makes your faculty/students such exceptional candidates for the Fulbright Program?

Our campus is both international- and service-oriented. Northwestern students work, live, and study with students from around the globe. Similarly, our faculty as a whole is deeply international in their background and their outlook. Our students confront and embrace the concept of “difference” daily and are comfortable asking questions that do not have easy answers. We have robust connections with our language faculty who participate on panels and promote the Fulbright Program to their students. Further, a spirit of service pervades this campus. It is rare to find a student who is not actively engaged in socially focused extracurricular activities. Add in the rigorous intellectual climate at Northwestern, and the result is that students are engaged with the world, have empathy for and curiosity about all people, and possess an inquisitive disposition—which, essentially, makes them great Fulbright applicants.

Northwestern’s many strengths are amplified by our culture of collaboration; our research and learning culture is deeply multidisciplinary. In a world where the greatest innovations are produced by teams, not individuals, Northwestern faculty and students are prepared to engage across disciplines and with international partners. This makes them excellent candidates for Fulbright awards because they approach the opportunity already coming from a culture of collaboration across boundaries of all kinds.

What steps have you taken to promote a Fulbright culture on your campus?

We work to keep Fulbright in front of students year-round. We joke that it is “always Fulbright season,” but this is more than a little true. Beginning with the national deadline, we communicate directly with last cycle’s non-recommended applicants and those who began, but did not finish, the application. We see both cohorts as likely candidates for the next cycle. Further, those students who go through our application process are our best advertisement! Our process really gets underway in January with a series of informational meetings which then morph into application workshops in May and June (Northwestern operates on a quarter schedule). In addition to specific Fulbright-focused events, nearly every conversation with students or presentation about fellowships uses Fulbright as an example. During the summer, students work closely with a Fulbright Program Adviser, whom we assign. This close relationship is in addition to their departmental mentors and cements their engagement with our office and the Fulbright application process.

How has your institution benefited from increased engagement with the Fulbright Program?

Northwestern University has been a consistent Fulbright Top Producing Institution for over a decade. Thanks to this record, most students and their faculty mentors see Fulbright as an excellent opportunity to further their interests. We are blessed with a good word-of-mouth network, which encourages students to develop an international outlook early in their education. Fulbright is a well-established aspirational goal for our students, and they see that their chances of receiving an award is within their grasp. They begin on-campus research experiences and language study knowing that developing these skills will help them to extend their local goals onto a global stage.

How does your institution support faculty and administrators who apply to the Fulbright Program?

For administrators who wish to apply to the Fulbright Program, Northwestern’s Office of International Relations promotes the opportunity and provides editorial feedback to staff on their applications.

For faculty, we connect prospective applicants with colleagues who have had Fulbright awards or who have hosted Fulbright representatives on campus and facilitate faculty members’ efforts to bring colleagues with Fulbright grants to campus when possible.

Find out more information about the ways that Northwestern connects with the Fulbright Program here.

What advice do you have for other universities and colleges that want to increase the number of Fulbrighters produced by their institution?

Success with the Fulbright Program starts with an internationally focused institution and strong faculty support. While individuals working with Fulbright applicants might not be able to single-handedly internationalize their campus, they can help faculty see the value in this program and in global opportunities as a whole. Through advertising, individual meetings, group meetings, and conclaves with appropriate faculty, an adviser can facilitate that moment when a faculty member taps a student on the shoulder and says, “You know, you should apply for a Fulbright.”