I’ve come to admire and enjoy so much about Indonesia since my first visit there in 1999 on an undergraduate semester abroad. Accordingly, returning on a Fulbright grant to conduct dissertation research on Indonesian migration to the United States was in many ways a homecoming. And, as every homecoming is often filled with new discoveries as well as pleasant familiarities, this one met — and then exceeded — my expectations.

I’ve come to admire and enjoy so much about Indonesia since my first visit there in 1999 on an undergraduate semester abroad. Accordingly, returning on a Fulbright grant to conduct dissertation research on Indonesian migration to the United States was in many ways a homecoming. And, as every homecoming is often filled with new discoveries as well as pleasant familiarities, this one met — and then exceeded — my expectations.

My Fulbright year began in November 2008 when I arrived in Jakarta to obtain my research permits with the help of the American Indonesian Exchange Foundation (AMINEF, Indonesia’s Fulbright commission). After completing these preliminaries and enjoying some time getting acquainted with the city, I was off to Surabaya, the nation’s second largest metropolis, to settle in and begin my fieldwork.

As I soon discovered, Surabaya is an especially exciting place in which to live and conduct historical research. Named the “City of Heroes” in honor of the valiant efforts of its citizenry during the Indonesian National Revolution, traces of the past linger on amidst a rapidly changing urban landscape. Places such as Tanjung Perak harbor, a working port since pre-modern times, the centuries-old ethnic residential settlements known as kampung, a diverse array of still-proud colonial-era buildings, and a wealth of archives, libraries, and museums make Surabaya an ideal site for an historian of any era.

In seeking to analyze episodes of Indonesian migration to the United States, I immersed myself in the city from which so many recent migrants originated and collected their stories. I spent time engaging in a variety of activities. Document hunting at the municipal archives and the Yayasan Medayu Agung library, recording former migrants’ original oral histories and conducting interviews with U.S. Consulate General staff in Surabaya, all yielded outstanding dissertation materials. Upon reviewing each of the sources I gathered, I’m reminded of the kindness and generosity shown to me during my fieldwork.

Beyond my research connections, additional encounters produced some of my most meaningful Fulbright moments. As a visiting lecturer in the Department of History at Airlangga University, my affiliate institution, I became part of a remarkable community. In appreciation and exchange for the University’s sponsorship, I co-taught seminars, mentored undergraduates, and helped organize an international academic conference on urban history. My colleagues’ unrivalled encouragement and support (and good–natured teasing about my Indonesian pronunciation) as well the opportunity to engage with an extraordinary group of students, are memories I continue to cherish. Off campus, volunteering as a cultural ambassador for the U.S. Consulate General brought me in contact with school children, journalists, and policy makers with whom I talked about life in the United States, Indonesians in America, and my Fulbright experiences. Representing my country in this capacity was truly an honor and has piqued my interest in pursuing a Foreign Service career.

My year in Indonesia prepared me not only to start writing my first dissertation chapters, but to also take on the next chapter of my life. Whether my next travels are to Indonesia or to somewhere entirely new, I’ll be able to transform any journey into a visit to a home away from home by drawing from my Fulbright experiences.

Tips for Prospective Study/Research Applicants:

- Design a feasible project and communicate your plans clearly in your application. When working on this step, ask: Can I reasonably carry out these plans within the parameters of the grant period? I found it helpful to envision and describe my project in terms of phases, each with some specific goals, and detail how I planned to accomplish each of them.

- Be proactive in reaching out to potential affiliates. Actively seek out affiliations by taking advantage of resources at your disposal, be they contacts at your college or university, online Fulbright resources, or other fonts of information. Once you come up with potential options, don’t be shy about getting in touch and inquiring about the possibility of an affiliation. Most organizations will be very happy to hear of your interest!

- Make the most of your affiliation(s). Once abroad, the organization(s) with which you are affiliated present a great opportunity to gain immersion in the country and culture in which you’re living. Spend time getting to know the people there and volunteering when and how you can. Not only will you achieve the grant objectives of increasing mutual understanding and promoting cross-cultural awareness, you may even gain some new friends and receive a good deal of research support.

- Be open to exploring. Whether it’s taking tips from local scholars on lesser-known research sites, allowing for variations in your schedule, or even trying different foods, don’t be afraid to step away from your proposed project agenda now and then to explore and experience new things.

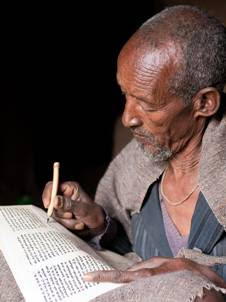

Photo: Dahlia Gratia Setiyawan, 2008–2009, Indonesia (second from right), with her colleagues in Airlangga University’s Department of History

Questions for Dahlia about her Fulbright experiences? Feel free to email her at DSetiyawan.AlumniAmbassador@fulbrightmail.org.